|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 16(11); 2019 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objective

This study was conducted to validate a Perceived Competence Scale for Disaster Mental Health Workforce (PCS-DMHW) designed to measure the core competences of mental health workers in disaster response situations at individual and organizational levels. core competences essentially required in disaster response situations were defined on the basis of literature review, focus-group interview with disaster response professionals, and expert judgment.

Methods

The preliminary items of the PCS-DMHW thus generated were administered to 509 participants consisted of mental health professionals and semi-professionals. The data retrieved from questionnaires were equally divided by two halves. The final items were determined through the exploratory factor analysis of the half data (n=255), and the construct validity was tested by performing the confirmatory factor analysis and criterion-related validity test of the remaining half data (n=254).

Any large-scale disaster induces fear, panic, sadness, despair or confusion not only to its direct victims and their families, but also to the local community and even the entire country. On the other hand, it also triggers healing-community reaction [1] seeking recovery and reconnection amidst crisis and chaos. Like many volunteers who work hard to restore their community, mental health professionals such as psychologists, psychiatrists, nurses, and social workers make a concerted effort to help survivors, family members, and others in the disaster area. Disaster mental health (DMH) workforce members can contribute to the recovery of survivors in their respective expertise and competence areas. Education and training are essential for them to play their roles well in disaster situations. Emphasis should therefore be placed on strengthening their expertise and competences as well as increasing a sense of responsibility for DMH services.

Competence can be to be understood as the effect that “a professional is qualified, capable, and able to understand and do certain things in an appropriate and effective manner” [2]. Competence is made up of a variety of elements, which can be summarized, for example, into what a person brings to a job or role (knowledge), what the person does in the job or role (performance), and what is achieved by the person in a job or role (outcomes) [3,4]. Recently, it has become a trend to extend the concept of competence by including ethic, value, and attitude that go beyond the scope of knowledge and skills [5-7]. The goal of education and training is to promote and develop these various competences, and the field of DMH is no exception.

The core competences required for disaster response are the elements essential for effective disaster-related task performance. In this regard, the Guidelines for International Trauma Training by ISTSS/RAND [8] present a series of rules and strategies that can be used as a basic framework for training lay health workers as well as professionals. The core elements of a DMH workforce training program are values and beliefs, contexts and systems, and an evidence-based curriculum [8]. DMH services involve experience and knowledge sharing in the traditional mental health field and require collaboration with other professionals, public officials and volunteers who have differing backgrounds and expertise. For this reason, organizational competences, in addition to individual competences, might be of vital importance in the field of DMH.

Many researchers have placed emphasis on the organizational competences of a DMH workforce, such as communication,9,10 leadership at extreme crisis [11], collaboration with other professionals [12,13], and teamwork [10]. Additionally, ethical competence is very important, given that DMH workforce members should deal with the existential and spiritual issues of the survivors, family members, and people in the community in extreme circumstances [8]. Therefore, a DMH workforce training and competence enhancement program should cover not only individual knowledge and skills but also ethic, attitudes, and values required of them as disaster survivors’ advocates and care providers, as well as organizational competences such as teamwork, leadership/followship and conflict management.

Thus far, core competences have been proposed for general healthcare or public health professionals and students, with focuses on psychological support and intervention as well as comprehensive disaster preparedness and response [9]. Regrettably, however, a scale for measuring core competences required of DMH workforce members, covering both individual and organizational competences, has yet to be developed. The delay in developing a DMH workforce competence scale may be ascribed to a number of reasons. First, the history of disaster is long, but the history of disaster research is relatively short. DMH is an emerging field with a short history compared with other disciplines. Therefore, it was not until recently that researchers became aware of the importance of the competences required of DMH workforce members and began to take interest in developing comprehensive and systematic training curricula. Accordingly, it is rather rarely the case that DMH or disaster psychology is offered as a required subject in the undergraduate or postgraduate curriculum of the related departments such as psychology, psychiatry, nursing and social work, and in the training courses for acquisition of professional licensure. However, the importance of the DMH field has been continually emphasized by several scholars [7,9], and each large-scale disaster has prompted increased attention to DMH. The second reason is associated with the lack of consensus on the definition of disaster response competences required of DMH workforce members. Related professionals, such as psychologists, physicians, nurses, and social workers, have their respective expertise and orientations, which makes it difficult for them to reach a consensus on common core competences in disaster situations. Whereas a few scales have been developed to measure the core competences in emergency nursing or urgent care situations [13-15] and emergency medicine [16], the core competences required of mental health professionals have not been established, still less a scale to measure them. Nonetheless, there is a growing demand for competence enhancement of the DMH workforce [17] with a constantly raising awareness of the need of developing an assessment tool to measure them.

Competence can be estimated with a fair degree of accuracy by objectively assessing the level of knowledge or skill-based performance, or by measuring the perceived competence, i.e., competence-related self-efficacy. The DMH competences can be accessed from a multidimensional perspective including a self-report and an observer rating methods and at individual and organizational levels. Perceived self-efficacy is one of the essential components for multidimensional assessment of the DMH competences. Workers with a high perceived competence are more likely to respond efficiently in actual disaster situations than those with a low perceived competence: there is a reciprocal relationship between actual response competence and perceived competence, i.e., the higher the former, the higher the latter [18,19]. Thus, the current study was intended to develop the Perceived Competence Scale for Disaster Mental Health Workforce (PCS-DMHW), a self-reported scale focusing on perceived competence related to disaster response, and to test its validity.

In Addition, most of the disaster response competence scales measure general competence without differentiating between individual and organizational competences. For example, in the study by Al Thobaity and colleagues [15] who developed a scale measuring the disaster nursing core competences, three factors were extracted, namely, core competences of disaster nursing, barriers to developing disaster nursing and nurses’ roles in disaster management. Of them, the core competences of disaster nursing include mitigation and planning and preparedness and response core competences. The Disaster Response Self-Efficacy Scale [14] for measuring nursing students’ disaster response competences consisted of disaster on-site rescue, disaster psychological nursing, and disaster role quality and adaptation. Notably, contrary to previous scales, the new PCS-DMHW has been designed to measure the perceived competence of both DMH professionals and lay health workers at the organization level, in addition to individual competences.

To sum up, this study pursues two objectives: 1) to develop a PCS-DMHW measuring the DMH workforce’s perceived core competences at both individual and organizational levels and 2) to test the construct validity and criterion-related validity of the PCS-DMHW using the empirical data collected from DMH workforce members.

The participants in this study consisted of 509 mental health professionals, para-professionals, volunteers at disaster site and postgraduate/undergraduate students of the related disciplines. Statistical analysis of all 509 respondents revealed that women outnumbered men (75.25-24.75%) amongst all respondents, the age bracket of 20-29 years was most frequent (43.62%), psychologists had the highest response rate (27.11%), and those with less than five years’ career (n=238, 46.76%) outnumbered those with longer career experience (n=169, 33.20%).

Supplementary Table 1 (in the online-only Data Supplement) presents the demographic characteristics of all respondents. Those who did not provide demographic information, but responded in good faith to the disaster response core competence questionnaire were included in the analysis. An expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm was applied to missing data. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of the Province (40525- 201506-HR-41-01) in Korea.

Development process of the PCS-DMHW took place in four steps.

The DMH workforce’s core competences, which are essentially required in disaster response situations, were extracted based on focus group interview (FGI), literature review, and expert judgment by the researchers. A total of 48 participants in the FGI were composed of 9 psychologists, 9 social workers, 6 psychiatrists, 11 nurses, 2 public officials, and 11 volunteers. The volunteers were divided almost evenly between those who had played roles as leaders or team members in disaster sites. Each session of FGI was held with five to six participants for a period of 2-3 hours. The participants reported their experiences of psychological support, disaster site management, case management, delivery of relief goods, or human resource management at disaster sites. They discussed required DMH competences, education or training curriculum and effective education methods at individual and organizational level. Based on analysis of the FGI discussions [20], core competences required in disaster response situations were extracted. Within the framework of the FGI, an attempt was made to empirically identify the sub-constructs and items pertaining to the core competences required in disaster response situations, and the FGI results were reflected in the design and classification of the preliminary items.

The core competences extracted from the FGI are classified into 9 sub-competences at the individual level and 7 subcompetences at the organizational level. The sub-competences at the individual level are as follows: 1) understanding of the disaster situation: disaster characteristics and survivors’ psychological state; 2) calling, sense of duty and sense of responsibility; 3) ethical and spiritual aspects; 4) self-care: prevention of burnout; 5) problem-solving ability and judiciousness; 6) communication, empathy and counseling ability; 7) information sharing : psychological education, information delivery to survivors, and institutional and practical information such as livelihood support; 8) assistance according to phase, timing, and intended beneficiaries (knowledge of tailored support); and 9) personal qualification of the DMH workers: flexibility, optimism, toughness and resilience. The sub-competences at the organizational level are as follows: 1) cooperation and teamwork; 2) leadership; 3) followship; 4) intra- and inter-organizational communication; 5) conflict management; 6) understanding of the disaster administration system; and 7) utilization of local resources and networking.

Based on the extracted disaster response core competences, preliminary items were written at the individual and organizational levels. Additionally, some items of the current existing measurement tool [21,22] were partially adopted as preliminary items. The original tool developed by Noh [22] and modified by Ahn and Kim [21] was modeled on the Framework of Disaster Nursing Competences published by the International Council of Nurses [23] and the Emergency Preparedness Information Questionnaire [24]. Some of the items of this tool were modified and supplemented, and then included as preliminary items.

The content validity of the extracted core competences was tested by a panel of experts consisting of 2 psychiatric nurses, 2 psychiatrists, 3 clinical psychologists and 1 mental health social worker. The appropriateness of sub-competences categories and the simplicity and clarity of preliminary items wording were reviewed by the panel. Most of the items represented well the content of their respective subscales, some items were modified reflecting the reviewers’ comments. For example, of the preliminary items at the individual level, “I received education related to psychological assistance in a disaster situation” was modified to “I have received systematic training in psychosocial support in disaster situations.” Also, for the item related to stress coping was added: “I am able to cope with the stress in the disaster site.” One organization-level preliminary item was modified from “I do not dump my duties on others in order not to disturb the organizational order” to “I do not dump my duties on others in a task-performance situation.” Consequently, a total of 99 preliminary items (56 individual competences, 43 organizational competences) were generated. The nine subscales of individual competences can be classified into three knowledge-aspect factors related to how to cope with disaster situations, three skill-aspect factors necessary for disaster response, and three attitudinal factors related to ethic, personal qualification and sense of calling. The seven subscales of organizational competences can be classified into teamwork ability required for smooth cooperation within the team in disaster situations, networking ability to connect local resources or administrative resources, and leadership and followship related to human resource management. Further analysis was performed based on these classifications.

The preliminary items, disaster nursing core competence scale, and Composite capacity indicators (CCI) [25] were concurrently administered to 255 participants. In a normality test prior to the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), all items were found to satisfy the usual normality assumption, with the skewness and Kurtosis of each item being lower than or equal to 3 and 10, respectively. The preliminary items selected in the first round were subjected to a first-order factor analysis by subscale at each of the subscales, whereby 4-9 items were classified into each subscale. The final items through for the subsequent EFA were determined by selecting three items for each of the subscales. The selected items represented well the content of their respective subscales and had the highest factor loadings. The final items of the PCS-DMHW were 24 items of the individual competence scale consisting of 15 knowledge and skill items (6 and 9 items, respectively) and 9 attitude items (ethic, characteristic, and sense of calling, three each) and 21 items of the organizational competence scale consisting of 12 teamwork items, 6 network items and 3 followship items. Although prevention of burnout was excluded from the EFA in the individual competence scale, three related items were included as a supplementary scale for future study, taking into account its importance at disaster sites. The selected items were the ones that best represented well the content of their respective subscales and had the highest factor loadings. The content and construct of each item and its reliability coefficient and the item analysis results are presented in Supplementary Table 2 (in the online-only Data Supplement).

Finally, the construct validity of the PCS-DMHW was assessed by performing the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and correlation analysis with other competence scales on the 254 participants. In addition, scores of the PCS-DMHW were compared according to the level of participants’ disaster response experience. The overall scale development process is presented in Table 1.

This 15-item tool was developed by Noh [22] to identify the core competences of medical staff in disaster situations and were modified and supplemented by Ahn and Kim [21]. It uses a 5-point Likert-type scale; the higher the score, the higher the disaster nursing core competence. For the purpose of this study, nursing or medical terms were replaced with their DMH equivalents. For example, “I know the duties of medical staff in a disaster case” and “I know the documentation process regarding the nursing services provided in disaster situations” were modified into “I know the duties of mental health workers in a disaster case” and “I know the mental health documentation process in a disaster case.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.900 in the study of Ahn and Kim [21] and 0.962 in this study.

This scale was developed by Reifels et al. [25] to determine the evidence-based intervention capacity of mental health professionals working at disaster sites. It is designed as true/false questions about psychological first aid, skills for psychological recovery, and intensive mental health treatments (training, interest, confidence, experience, ability, and understanding of disaster), whereby the higher the score, the higher the intervention capacity. The Cronbach’s α was 0.911 in the study of Reifels et al. [25] and 0.911 in this study.

The questionnaires were distributed and retrieved mainly at psychiatric clinics, community mental health centers, disaster recovery support centers, mental health-related university departments and academic conferences hall for mental health professionals in Korea. The questionnaire was administered by post or in a face-to-face manner. After signing the informed consent form, participants completed self-report questionnaires that assessed socio-demographic characteristics, career and DMH competences. Respondents needed approximately 15 to 20 minutes to complete the developmentstage questionnaire. Among the participants, 40 graduate students were re-tested for PCS-DMHW 2 weeks after the first test.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to describe the demographic characteristics of the study participants and to determine the interrelatedness between each subscale and other disaster mental health-related variables.

For EFA, we applied principal axis factoring, which is a factor extraction method less sensitive to non-normal data, and direct oblimin rotation under the assumption of intercorrelations among factors. Parallel analysis and scree plot were used to determine the appropriate number of factors. For the CFA, we established the inter-variable correlations, drawing on the initial theoretical model and the results of the EFA, and tested the model fit. The χ2 test was carried out for model fit analysis. Also used were the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation Index (RMSEA), whereby values ≥ 0.90, ≥0.90, and <0.8, respectively, were considered to be indicative of good fit [26].

The criterion-related validity was verified by the results of correlation analysis between the PCS-DMHW, CCI and disaster nursing core competence scale. ANOVA was performed to determine the differences in scores of the PCS-DMHW depending on length of career.

EFA was undertaken on all 24 items of the PCS-DMHW at the individual level, consisting of knowledge, skill and attitude. Factors were extracted using principal axis factoring and orthogonalized using direct oblimin rotation under the assumption of inter-correlations among factors. As the criteria for factor extraction, we applied the factor loading cutoff value of 0.30 for a given item and the factor loading difference of ≥0.10 with respect to other items, as proposed by Floyd and Widaman [27].

In the next step, the results of parallel analysis and scree plot were examined to determine the adequate number of factors, and four was recommended as the number of possible factors. Supplementary Figure 1 (in the online-only Data Supplement) presents these analysis results. The EFA using the principal axis factoring (oblimin rotation) revealed that these four factors accounted for 59.01% of the total variance, with the first factor accounting for 44.32%, the second factor for 7.85%, the third factor for 3.85%, and the fourth factor for 3.26%. Each item’s factor loading ranged from 0.415 to 0.853 (Table 2). The first factor was named ‘perceived competence of knowledge and skill’. Other three factors were associated with the attitude required at disaster sites and named ‘ethic’, ‘qualification’ and ‘sense of calling’, respectively. In the case of item #15 (problem solving), although the factor loading exceeded 0.30 for more than two factors, it was judged appropriate to include it in factor 1 because the factor loading difference exceeded the cut-off value of 0.10.

Table 2 outlines the factor loading, commonality, and internal consistency of the items as classified into the four factors. Cronbach’s α, which expresses the reliability of the total individual competence scale, was 0.947, and the test-retest reliability coefficient for 2-week interval was 0.637 (n=40).

The EFA was performed on all 21 items of the PCS-DMHW at organizational level, consisting of teamwork, network and human resource management. The results of parallel analysis and scree plot were examined to determine the adequate number of factors, and three was recommended as the number of possible factors. Supplementary Figure 1 (in the online-only Data Supplement) presents these analysis results. EFA was then performed on each subscale, with the number of the factors set at three (Table 3). As a result of the EFA, these three factors were found to account for 62.13% of the total variance, with the first factor accounting for 52.85%, the second factor for 7.85%, and the third factor for 3.66%. Each item’s factor loading ranged from 0.426 to 0.936, with none of the items showing values exceeding 0.30 in two or more factors. The three factors were named ‘teamwork’, ‘network’ and ‘followship’, respectively.

Cronbach’s α, which expresses the reliability of the total organizational competence scale, was 0.956, and the test-retest reliability coefficient for 2-week interval was 0.624.

The correlations between the subscales of the PCS-DMHW were analyzed and the results are shown in Table 4. Except for subscale ‘ethic’, which had relatively low correlation with other subscales, the PCS-DMHW showed generally high inter-factor correlations (r=0.49-0.74) among all other subscales, which suggests that the core competences for DMH are closely associated with one another.

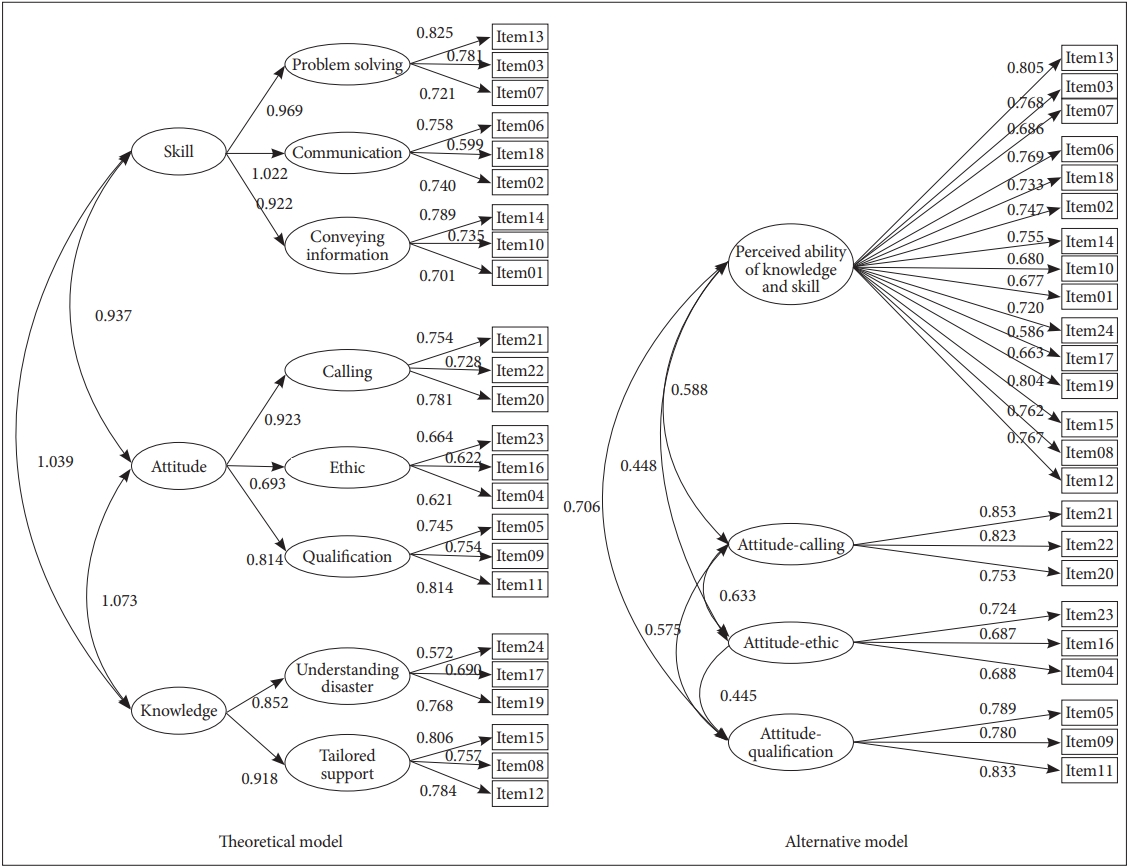

In another sample of 254, the CFA of the individual/organizational competences scales was performed. The initial theoretical model of the individual competences set out three factors, namely, knowledge, skills and attitude, the EFA yielded a four-factor structure consisting of perceived competence of knowledge and skills, ethic, personal qualification and sense of calling. As shown in Figure 1, both the initially hypothesized hierarchical three-factor structure model (theoretical model) and the four-factor alternative model derived from the EFA were subjected to CFA.

As presented in Table 5, the fit indices of the alternative model were within acceptable limits. The theoretical model which is a hierarchical model consisting of three factors of knowledge, skills and attitude, yielded lower values than the alternative model in all these fit indices. The ratio of chi square to its degrees of freedom (χ2/df) verified both models to fit well with the data, yielding the values placed within the range of 2-5 [28], and thus the alternative model can be considered to be a suitable model. In the theoretical model, a Heywood case with negative error dispersion was found. Because of this, it was difficult to adopt this model. In other words, the alternative model demonstrated the best model fit with χ2 (246)=602.05, p<0.001, and RMSEA=0.075 (0.068-0.083). A comparative analysis of two models revealed significant differences in the degrees of freedom (5) and χ2 (182.27; χ2 significance level threshold=11.07), thus favoring the alternative model. With the TLI value exceeding 0.85, it can be conclusively confirmed that the alternative model is a better fit.

While the organizational competences scale comprised three factors of teamwork, network and human resource management in the initial theoretical model, a three-factor structure consisting of competences of team work, network and followship was established as a result of EFA. As shown in Figure 2, the CFA was performed for both the initially hypothesized hierarchical three-factor structure model (theoretical model) and the three-factor alternative model derived from the EFA.

As presented in Table 6, the fit indices of the alternative model were calculated at CFI=0.933, TLI=0.922, and RMSEA=0.068, which are all within the acceptable ranges. In contrast, the initial theoretical model, showed lower values in all three indices. In theoretical model, a Heywood case with negative error dispersion was found. Because of this, it was difficult to adopt a model.

The three-factor structure derived from the alternative model was found to have the best fit of χ2 (180)=393.26, p< 0.001, and RMSEA=0.068 (0.059-0.078). A comparative analysis of two models revealed significant differences in the degrees of freedom (1) and χ2 (26.44; χ2 significance level threshold=3.84), thus favoring the alternative model. With a relatively high parsimony and the CFI and TLI values exceeding 0.90, it can be conclusively confirmed that the alternative model is a better fit.

To verify criterion-related validity after categorizing the respondents’ career levels into 1) no career, 2) less than 5 years of career, and 3) at least 5 years of career after obtaining the professional qualification, ANOVA was conducted to compare scores on the PCS-DMHW among these three groups (Table 7). After the exclusion of two respondents who didn't answer the question about length of career, the analysis was performed on the data extracted from 252 respondents.

In the case of the individual competences, the higher career level group (≥5 years) reported higher perceived competence in the knowledge and skills subscale [F (2,249)= 7.913, p=0.000]. However, there were no significant differences among groups depending on a length of career in the attituderelated subscales. As for the organizational competences, the higher career level group reported higher perceived competence in the teamwork and network competences [F (2,249)= 3.153, p=0.044; F (2,249)=5.407, p=0.005]. However, there were no significant differences among groups depending on a length of career in the followship competence.

This study was conducted to develop and validate the PCS-DMHW, a scale capable of measuring the perceived core competences of DMH workforce members at individual and organizational levels. This self-reported scale includes 24 items classified into four subscales of individual competences (knowledge and skill, ethic, personal qualification, and calling), 27 items classified into three subscales of organizational competences (teamwork, network, and followship), and three items pertaining to one supplementary scale (prevention of burnout).

In the process of testing the content validity of the theoretical model of the PCS-DMHW, the individual competences, which were classified into three sub-competences of DMH support-related knowledge, skills required for disaster response, and essentially required attitudes, were reclassified through EFA into four factors as follows: knowledge and skill were extracted together as a single factor, and attitudes were distinctively categorized into three factors of ethic, characteristic, and calling. These four individual competence factors were also verified by CFA.

The knowledge and skills items within the individual competences scale were extracted into one factor in the EFA. This result suggests that knowledge and skills are regarded theoretically as separate concepts, but the two operated interactively in disaster response situations, instead of independently from each other. Contrary to our expectations, the items pertaining to the subscale “prevention of burnout” as part of individual competences were excluded from analysis because they failed to be grouped together into a single factor and the overall model fit was poor when they were included in the CFA. Despite the insufficient statistical relevance of the ‘prevention of burnout’ subscale, it was decided to retain the related items as a supplementary subscale for future studies in consideration of the absolute importance of preventing of burnout at disaster situations.

As regards the organizational competence scale of the PCS-DMHW, three factors of teamwork, network and followship were found to be appropriate theoretically and empirically fit in both EFA and CFA. Among the organizational competences essential when working at disaster sites, leadership, communication, cooperation and conflict management were grouped together into the factor ‘teamwork’, resource networking and disaster administration into the factor ‘network’, and followship was classified as a separate single factor. In the theoretical model of the PCS-DMHW, leadership and followship were assumed to form one factor related to human resource management, but the leadership factor was included in the teamwork scale measuring communication, cooperation and conflict management in the final model. The ‘teamwork’ scale of the PCS-DMHW is also in good agreement with the findings of previous studies, according to which the most common teamwork component is the informationsharing communication among team members [29,30] and team leadership is the decisive factor for promoting effective teamwork [31,32]. I Inclusion of the ‘network’ and ‘followship’ subscales in the PCS-DMHW is considered to be associated with the specific situation of disaster. The ‘network’ subscale reflects well the importance of networking the human and material resources generally scarce in disaster situations and the need for administrative competence for resource networking. The scale labeled ‘followship’ refers to the ability to follow leaders’ instructions and accomplish the task assigned.

Correlation analysis was performed to test discriminant and convergent validity, whereby it was anticipated that subscales within the PCS-DMHW, either individual or organizational, would have higher correlations. While the interscale correlation of the PCS-DMHW was found to be fairly high, the subscales at the individual level showed high positive correlations not only with other individual competences, but also with organizational competences. Interestingly, ‘ethic’ subscale showed lowest correlation with the subscale ‘knowledge and skills’ among all individual competence subscales and relatively high correlations with ‘teamwork’ and ‘followship’ subscales among organizational competences. These suggest that the attitude of respecting survivors’ human rights and providing ethically appropriate care for them in disaster situations is also associated with the capacity to respect colleagues with different backgrounds and cooperate well with them. The organization-level subscales showed relatively high intra-scale correlations. Among the organizational competence subscales, ‘teamwork’ demonstrated relatively high positive correlations not only with ‘network’ and ‘followship’ but also with the individual competence subscales. It suggests that individual and organizational competences are interdependent. A high correlation was also demonstrated between the subscales ‘knowledge and skills’ and ‘network’, which is presumably associated with the actual task performance and role assumption among DMH workforce members in disaster situations.

The PCS-DMHW scores were compared according to the length of career of the participants to verify criterion-related validity. While no significant career-dependent differences were shown in the perceived competences of ‘ethic’, ‘qualification’, ‘a sense of calling’, and ‘followship’, the higher career group (≥5 years after obtaining professional qualification) yielded significantly higher scores in the subscales of ‘perceived knowledge and skills’ and ‘network’ compared with the lower career or no career groups. Given that these two subscales are related to the main tasks and roles of the DMH workforce in disaster situations, it may be assumed that career level has influence on the perceived competence in the actual work-related factors, not in the attitude factor of the DMH workforce members. The higher career level group (≥ 5 years) scored higher in ‘teamwork’ competence as well compared with the lower career level group (<5 years). These results partially support the validity of the PCS-DMHW.

Under the examination as presented above, the PCS-DMHW is successfully measuring perceived individual and organizational competences in the field of DMH. It has demonstrated relatively high reliability and validity. Although the sample utilized in this study is not from a normative dataset of mental health workers in Korea, it seems useful as an indicator of the need for improvement training in DMH competences based upon a standard score (e.g., T-score) drawn from mean and standard deviation of our participants. It should be cautiously suggested that training of the competences for disaster response is needed if the individual competence is less than 31 points or the organizational competence is less than 40 points (35 T-score).

In terms of scale development and construct, however, this instrument has several limitations. First, although the items of the PCS-DMHW, were generated after a thorough investigation through literature review and expert FGI, DMH being an emerging field with a relatively short history, no theoretical and empirical consensus has yet been reached among experts and professionals as to its core competences. Moreover, while there has been relatively extensive research on multidisciplinary teamwork in the medical field, teamwork has attracted little attention in the psychology field except in the subfield of organizational psychology. Therefore, continuous efforts will have to be undertaken to bring about theoretical and conceptual consensus on the core competences required of mental health workers for disaster response respond.

Second, Costello and Osborne [33] argue that a stable factor structure can be established only if at least four items are included in one factor. However, according to MacCallum et al. [34], at least three items are necessary to construct a factor properly. Relying on this, the PCS-DMHW was constructed with three items per factor in the preliminary research of this study lest the number of items should exceed the range of smooth survey administration by including four or more items in a factor.

Third, considering that the minimum number of samples is 50 and that the number of samples should be four- to fivefold the number of variables to be tested as prior conditions generally required for factor analysis, the minimum necessary number of samples for a disaster response core competence scale would be 180-225 (45 items×4-5). Based on this calculation, the number of samples for EFA and CFA was set at around 250 each. However, in the case of CFA, a minimum of 300 participants have been recommended [35]. Therefore, it is considered necessary to establish a more robust factor structure by conducting a CFA of the proposed scale on a larger number of mental health professionals.

Fourth, the PCS-DMHW does not directly measure the knowledge and skills actually required at disaster sites and the ability to work with colleagues. However, it may be considered a useful scale in terms of benefit-cost ratio, given the positive relationship between perceived competence and actual response capacity [18,19]. In order to help develop and strengthen more efficiently the competences of DMH workforce members, there is a need to assess their competences using various methods in addition to a self-reported scale.

Finally, the PCS-DMHW was developed and validated for Korean mental health workers. Korea has a short history of systematic response to large-scale disasters, and there are a relatively small number of professionals with experience in disaster response. In this study, the respondents’ PCS-DMHW scores were compared after classifying them into three groups according to the length of time after obtaining professional qualifications (no career, <5 years, and ≥5 years). However, it is necessary to compare the PCS-DMHW scores among groups classified according to the degree of experience or actual ability in disaster response in future studies. Also, the discriminant and convergent validity will have to be tested through correlation analysis with other competence scales. The applicability of the PCS-DMHW in other cultures and languages will also have to be investigated.

Despite the above-described limitations, the PCS-DMHW is the only tool known to the researchers for measuring the perceived competences of professionals from various fields and lay health workers in the field of DMH, not limited to specific occupation groups. Furthermore, items of the PCS-DMHW were developed at both individual and organizational levels so that it may be used in various education and training settings. The PCS-DMHW is expected to serve as a useful tool in the education and training programs aiming at developing and strengthening the DMH workforce’s professional capacity.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2019.0140.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant of the Korean Mental Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HM15C1189).

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Hyae-young Yoon, Yun-Kyeung Choi. Data curation: Hyae-young Yoon. Formal analysis: Hyae-young Yoon. Funding acquisition: Yun-Kyeung Choi. Investigation: Hyae-young Yoon, Yun-Kyeung Choi. Methodology: Hyae-young Yoon. Supervision: Yun-Kyeung Choi. Writing—original draft: Hyae-young Yoon, Yun-Kyeung Choi. Writing—review & editing: Yun-Kyeung Choi.

Table 1.

Development and validation process of the perceived competence scale for disaster mental health workforce

Table 2.

Result of exploratory factor analysis: competence in individual level (N=255)

Table 3.

Result of exploratory factor analysis: competence in organization level (N=255)

Table 4.

Correlation between disaster mental health competence sub-scales (N=255)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competence in individual level | |||||||

| 1. Perceived ability of knowledge and skill | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Attitude ; ethic | 0.379* | 1 | |||||

| 3. Attitude ; qualification | 0.651* | 0.392* | 1 | ||||

| 4. Attitude; calling | 0.584* | 0.486* | 0.529* | 1 | |||

| Competence in organization level | |||||||

| 5. Team work | 0.634* | 0.559* | 0.709* | 0.573* | 1 | ||

| 6. Network | 0.785* | 0.354* | 0.602* | 0.550* | 0.738* | 1 | |

| 7. Followship | 0.487* | 0.588* | 0.533* | 0.506* | 0.708* | 0.607* | |

| Mean | 31.21 | 9.93 | 7.65 | 8.39 | 33.35 | 14.04 | 9.24 |

| SD | 10.77 | 1.92 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 7.34 | 4.79 | 2.00 |

Table 5.

Result of confirmatory factor analysis: the disaster mental health competence scale in individual level (N=254)

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | Lo90 | Hi90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | ||||||||

| Theoretical model | 784.32 | 241 | 3.254 | 0.830 | 0.851 | 0.094 | 0.087 | 0.102 |

| Alternative model | 602.05 | 246 | 2.447 | 0.891 | 0.903 | 0.075 | 0.068 | 0.083 |

Table 6.

Result of confirmatory factor analysis: the disaster mental health competence scale in organization level (N=254)

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | Lo90 | Hi90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organization | ||||||||

| Theoretical model | 419.70 | 179 | 2.35 | 0.927 | 0.938 | 0.073 | 0.064 | 0.082 |

| Alternative model | 393.26 | 180 | 2.19 | 0.922 | 0.933 | 0.068 | 0.059 | 0.078 |

Table 7.

Differences of disaster mental health competence scale according to career of the participants (N=252)

REFERENCES

1. Steffen SL, Fothergill A. 9/11 volunteerism: a pathway to personal healing and community engagement. Soc Sci J 2009;46:29-46.

2. Rodolfa E, Bent R, Eisman E, Nelson P, Rehm L, Ritchie P. A cube model for competency development: implications for psychology educators and regulators. Prof Psychol Res Pract 2005;36:347-354.

3. Proctor J. Using Competences in Management Development. Bristol: Henley Distance Learning Limited; 1991.

4. Reilly DH, Barclay J, Culbertson F. The current status of competencybased training, part 1: validity, reliability, logistical, and ethical issues. J School Psychol 1977;15:68-74.

6. McIlvried EJ, Bent RJ. Core Competencies: Current and Future Perspectives. In: Annual Conference of the National Schools and Programs in Professional Psychology; Scottsdale, AZ. 2003.

7. Walsh L, Subbarao I, Gebbie K, Schor KW, Lyznicki J, Strauss-Riggs K, et al. Core competencies for disaster medicine and public health. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2012;6:44-52.

8. Eisenman D, Weine S, Green B, Jong Jd, Rayburn N, Ventevogel P, et al. The ISTSS/Rand guidelines on mental health training of primary healthcare providers for trauma‐exposed populations in conflict‐affected countries. J Trauma Stress 2006;19:5-17.

9. Hsu EB, Thomas TL, Bass EB, Whyne D, Kelen GD, Green GB. Healthcare worker competencies for disaster training. BMC Med Educ 2006;6:19

10. King RV, North CS, Larkin GL, Downs DL, Klein KR, Fowler RL, et al. Attributes of effective disaster responders: focus group discussions with key emergency response leaders. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2010;4:332-338.

11. Wheeler CM, Weeks PP, Montgomery D. Disaster response leadership: perceptions of American red cross workers. Int J Leadersh Stud 2013;8:79-100.

12. Lakanmaa R, Suominen T, Perttilä J, Puukka P, Leino-Kilpi H. Competence requirements in intensive and critical care nursing-still in need of definition? A Delphi study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2012;28:329-336.

13. Takase M, Teraoka S. Development of the holistic nursing competence scale. Nurs Health Sci 2011;13:396-403.

14. Li H, Bi R, Zhong Q. The development and psychometric testing of a Disaster Response Self-Efficacy Scale among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 2017;59:16-20.

15. Al Thobaity A, Williams B, Plummer V. A new scale for disaster nursing core competencies: development and psychometric testing. Australas Emerg Nurs J 2016;19:11-19.

16. Shayne P, Gallahue F, Rinnert S, Anderson CL, Hern G, Katz E. Reliability of a core competency checklist assessment in the emergency department: the Standardized Direct Observation Assessment Tool. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:727-732.

17. Yutrzenka BA, Naifeh JA. Traumatic stress, disaster psychology, and graduate education: reflections on the special section and recommendations for professional psychology training. Train Educ Prof Psychol 2008;2:96-102.

18. Bandura A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J Soc Clin Psychol 1986;4:359-373.

19. Artino AR. Academic self-efficacy: from educational theory to instructional practice. Perspect Med Educ 2012;1:76-85.

20. Shim SM, Yoon HY, Choi YK. Lessons from the experiences of volunteers at the Sewol Ferry disaster. Korean J Stress Research 2017;25:105-119.

21. Ahn E, Kim S. Disaster experience, perception and core competencies on disaster nursing of nursing students. J Digit Converg 2013;11:257-267.

22. Noh JY. Nurse’s Perception and Core Competencies on Disaster Nursing Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Seoul, Yonsei University. 2010.

23. Lee Y, Lee M, Park S. Development of the disaster nursing competency scale for nursing students. J Korean Soc Disaster Inform 2013;9:511-520.

24. Wisniewski R, Dennik-Champion G, Peltier JW. Emergency preparedness competencies: assessing nurses’ educational needs. J Nurs Adm 2004;34:475-480.

25. Reifels L, Naccarella L, Blashki G, Pirkis J. Examining disaster mental health workforce capacity. Psychiatry 2014;77:199-205.

27. Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychol Assess 1995;7:286-299.

28. Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for Structural Equation Modeling: A Researcher’s Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

29. Valentine MA, Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Measuring teamwork in health care settings: a review of survey instruments. Med Care 2012;53:e16-e30.

30. Valentine MA, Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Measuring teamwork in health care settings: a review of survey instruments. Med Care 2015;53:e16-e30.

31. Regan S, Laschinger HK, Wong CA. The influence of empowerment, authentic leadership, and professional practice environments on nurses’ perceived interprofessional collaboration. J Nurs Manag 2016;24:E54-E61.

32. Taplin SH, Foster MK, Shortell SM. Organizational leadership for building effective health care teams. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:279-281.

33. Costello A, Osborne J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval 2005;10:1-9.

34. MacCallum RC, Widaman KF, Zhang S, Hong S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychol Methods 1999;4:84-99.

35. Yong AG, Pearce SA. Beginner’s guide to factor analysis: focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Quant Methods Psychol 2013;9:79-94.

- TOOLS