|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 12(4); 2015 > Article |

Abstract

Objective

The Modified Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR-M36) scale was developed for medically ill, older individuals in 2008 (Toronto, Canada, department of psychosocial oncology and palliative care, Princess Margaret Hospital). The scale has displayed satisfactory reliability and validity. This study aimed to test the reliability and validity of the Korean version of Modified Experiences in Close Relationships (K-ECR-M36) questionnaire in female patients with breast cancer.

Methods

A total of 199 post-operative breast cancer patients completed the K-ECR-M36 as well as other psychological measures including the Revised Adult Attachment Scale (RAAS), World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale Abbreviated Version (WHOQOL-BREF), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The reliability and validity of the K-ECR-M36 were evaluated. Explorative factor analysis was conducted to identify the factor structure of the K-ECR-M36.

Results

The K-ECR-M36 showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α=0.87) and reasonable test-retest reliability (r=0.752, p<0.001). The total as well as avoidance and anxiety subscales demonstrated construct validity with the RAAS, the HADS, and the WHOQOL-BREF. Factor analysis revealed four-factor structure which was originally proposed by Brennan, Clark, and Shaver (1998).

The attachment system is hypothesized to be an evolutionally based biological mechanism that drives infants to seek proximity to the primary attachment figure (or caregiver) in cases of danger or need. Based on the child's reciprocal action with their chief caregivers, internal working models of self and others are formed. In particular, the accessibility and responsiveness of the attachment figure to the infants' emotional signals are considered pivotal for this process.12 The responsiveness and accessibility, if it is present and positive, can provide an infant with a secure emotional base. This secure base allows the infant to explore their world, develop expectations, and handle stressful situations. Bowlby first developed and proposed attachment theory. Ainsworth appropriated the theoretical base to develop the first instrument to measure patterns of infant-parent attachment: The instrument, termed 'a strange situation' identified three types of infant personality: secure, anxious/ambivalent, and avoidant.3

Hazan and Shaver4 applied Ainsworth's three styles of infant attachment to their research into adult attachment. They considered how adults with different attachment histories would classify themselves according to the ways they think, feel, and behave in close relationships. They argued that the three attachment patterns seen during infancy would emerge as three primary interpersonal styles during adolescence and adulthood.4 As adults, those who are securely attached go through unsuspecting and long-period relationships. Other major characteristics of securely attached individuals involve having great self-esteem, relishing close relationships, pursuit social support and a capability to share emotions with other people. Attachment is an important concept not only for children, but also for adults in this aspect. Adult attachment has become a major focus of research in the areas of personality, social, clinical, counseling, and developmental psychology.

The regulation of emotion is regarded as the central tenet of attachment theory. Significance of affect regulation is apparent in severe chronic illnesses such as cancer. Patients may feel the emotional need to rely on physicians and intimate relationships in order to make appropriate decisions and alleviate distress. A close relational bonding has a protective impact on emotional and physical health, including restoration of immune competence as well as mediating optimal coping with adversities including chronic illness.5 Low anxiety regarding relationships and a high comfort with closeness are protective factors for depression in the context of chronic pain and illness. Secure attachment may clinically present with lower levels of depression compared with less secure patients and may be less vulnerable to the disabling interaction between mood disturbance and chronic illness.6

A number of validated measurements of adult attachment exist in the literature: Two of the most recent of the self-report measures having high internal consistency are the ECR and the ECR-R. There now appears to be a consensus the adult attachment consist of these two dimensions: Anxiety and Avoidance.7

In 1998, Simpson et al.8 developed the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) measure, a 36-item questionnaire based on two dimensions: anxiety and avoidance. The ECR scale has been used worldwide in many countries in their local language version. However, ECR has not been suitable for a population that may be older and suffering from a considerable disease burden since the terms 'romantic partners'. Although secure attachment is one crucial prognostic factor for cancer patients, it may be difficult to assign study participants an attachment score if the ECR is administered to a population with-out romantic partners (e.g., older adults, medically ill patients who live alone). In this respect the department of psychosocial oncology and palliative care, Princess Margaret Hospital in Toronto, Canada, developed the Modified Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR-M36). The scale was used for patients with metastatic gastrointestinal and lung cancer completing the ECR-M36 and other scales tapping self-esteem, social support and depressive symptoms at two occasions within a period of 4 to 6 months. The scale shows a credible internal consistency, the test-retest reliability and validity were satisfactory as well (Supplement 1 in the online-only Data Supplement).9

In Korean females, the most common cancer sites were the thyroid (crude rate=596.9) and the breast (crude rate=413.4).10 The number of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer increased 2.5-fold in recent 8 years and breast cancer became the second most common cancer in women in Korea.11 The disease burden of breast cancer has recently increased in Korea. The global burden of breast cancer doubled between 1975 and 2000.12 The trend of increasing incidence of breast cancer should continue globally; the trend will be particularly evident in Korea where the average age of diagnosis is declining compared to Western countries. A patient's body image is also a problematic concern in breast cancer patients, particularly in younger women.13 Breast cancer is a significant and growing issue in terms of disease burden, early onset age(pivotal period), and a symbolic organ. Thus, breast cancer patients face a substantial psychiatric stress load along with physical pain. Appropriate psychiatric assessment and support is essential to help manage the current disease burden in Korea. In this context, breast cancer patients were chosen as a suitable study population to test the Korean version of the ECR-M36 (K-ECR-M36). This study aimed to develop the K-ECR-M36 and establish its psychometric properties.

The participants consisted of 216 post-operative breast cancer patients, given a hand in a large study of psychosocial adjustment performed by the Mental Health Assessment and Support Team (MHAST) for breast cancer at the Kyungpook National University Hospital (KNUH) and in the comprehensive medical team of breast cancer center at the Kyung-pook National University Medical Center (KNUMC), Daegu, Korea. A group of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients who were hospitalized in the KNUH and KNUMC were registered following their surgery between July 2010 and June 2013. First of all, we explained the objective and procedure of our study to the patients and then interested patients were entitled to take part if they met the following conditions: newly diagnosed breast cancer, undergone breast surgery, no other critical medical or psychiatric diseases, female aged between 18 and 80 years, capable to give a written informed consent and literate Korean.

Among the 216 patients, 17 subjects who partially completed the K-ECR-M36 were excluded from the study. In the final analysis, the study participants consisted of 199 patients. This study was recognized by the Institutional Review Board of the KNUH. All participants were offered written informed consent after sufficient explanation.

The ECR-M36 is a modified version of the original 36-item ECR questionnaire to evaluate the attachment to close others rather than to romantic partners only. Modification was achieved by replacing relevant items, the terms 'other people' or 'people with whom I feel close' in substitute for 'romantic partner(s)'; and by adding the instruction that the term 'other people' refers to people with whom the patient feels close. The ECR-M36 scale was originally developed for medically ill, older individuals in 2008 (Toronto, Canada, department of psychosocial oncology and palliative care, Princess Margaret Hospital) showing satisfactory reliability and validity.8 Time 1 internal reliabilities for the anxiety and avoidance subscales were high with Cronbach's α of 0.91 and 0.88, respectively. Time 2 internal reliabilities were the same as Time 1 internal reliabilities. According to the developers of the ECR, a low score could be considered as a secure attachment.7 The ECR-M36 is interpreted in the same way and is also composed of two dimensions including anxiety (even number items) and avoidance (odd number items). Participants use a 7-point Likert scale (1 'disagree strongly', 7 'agree strongly') to rate their agreement with statements based on their experiences in close relationships.9

The Revised Adult Attachment Scale (RAAS) is an18-item self-report screening scale that was developed to indicate the attachment styles by Collins, 1996. Each item scores on a 5-point Likert scale. The scale scores from 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (very much like me). The scores for the six items relating to each of the original attachment styles were summed to produce a score for that attachment style, ranging from 6 to 30.1415

The Korean version of RAAS has already been developed and its validity and reliability has already been proven.16

The RAAS yields three subscales: comfort with emotional closeness, comfort with depending on or trusting in others and anxious concern about being abandoned or unloved. Participants are asked to respond in terms of their general orientation towards close relationships. Simpson et al.8 found that the first two factors correlate with an avoidance dimension (r=0.86 and r=0.79, respectively) and that the latter correlates with an anxiety dimension of other self-report attachment scales (r=0.74).

Based on this research result, correlation analyses were used to examine the relationship between the 12 items of dependence, closeness subscales (high score signified more secure attachment) and the avoidance dimension of the ECR-M36, between 6 items of anxiety subscale (low score signified more secure attachment) and the anxiety dimension of the ECR-M36 in our study.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is composed of a 14-item self-report screening scale that was originally developed to indicate the possible presence of anxiety and depression states in the setting of a medical non-psychiatric outpatient clinic.17 It was primarily exploited by Snaith and Zigmond.17 Since the scale is quite brief and simple, it has been widely used by not only psychiatrist but also non-psychiatric doctors.

The HADS is composed of two subscales. Odd number is a 7-item anxiety subscale (HAD-A) and even number is a 7-item depression subscale (HAD-D). Each item uses a 4-point Likert scale, giving maximum subscale scores of 21 for depression and anxiety, respectively (0-7=normal, 8-10=borderline abnormal, 11-21: abnormal). The Korean version of HADS was employed in this study for the assessment of construct validity. It has already been proven to have a satisfactory internal consistency. Cronbach's α values were 0.89 for the HAD-A and 0.86 for the HAD-D.18

We applied the Korean version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale Abbreviated Version (WHOQOL-BREF) to assess the patient's understanding of their own QOL. This scale showed satisfactory reliability and validity in the application in the Korean population according to the guideline of the WHOQOL group. It is composed of 26 items: 24 items for four domains (psychological, physical health, social relationships, and environment) and 2 items for the overall QOL and general health. It uses a 5-point Likert scale in which higher scores indicate higher QOL. The Cronbach's α for total score was 0.898 and α value for domain score ranged from 0.583 for domain 3 to 0.777 for domain 1.19

We employed a forward backward translation method, according to the EORTC Quality of Life Group Translation Procedure. In this way was the K-ECR-M36 formed.

The authors of the K-ECR-M36 are native Korean who are fluent in English and individually translated the 36 items of the English version of the ECR-M36. Both interpreted versions were then compared and the first Korean version was acquired after discussing and analyzing the points of similarities and differences. A native English speaker subsequently translated the preliminary Korean version back to English without reference to the ECR-M36.

To complete an understandable instrument that is conceptually consistent with the ECR-M36, the two versions (back-translated and original ECR-M36) were balanced and translation difficulties were analyzed and resolved between the translators. Unique characteristics of Korean culture and language were considered through translating and adapting this instrument.

The first Korean version of ECR-M36 was delivered to a pilot group of 20 breast cancer patients in order to confirm and solve any potential problems in translation. Patients were requested to evaluate about understandability of each item after finishing the questionnaire. Generally, patients showed a good comprehensibility of items and had no critical difficulties in responding to the questionnaire. The final Korean version of the ECR-M36 was then attained (Supplement 2 in the online-only Data Supplement).

Descriptive data were obtained for all demographic and clinical characteristics for the global sample. Cronbach's α was calculated to evaluate the internal reliability of the K-ECR-M36. Test-retest reliability was calculated using Pearson's correlation analysis. Pearson's correlations between the ECR-M36 and other measures (HADS, WHOQOL-BREF, and RAAS) were calculated to explore the construct validity.

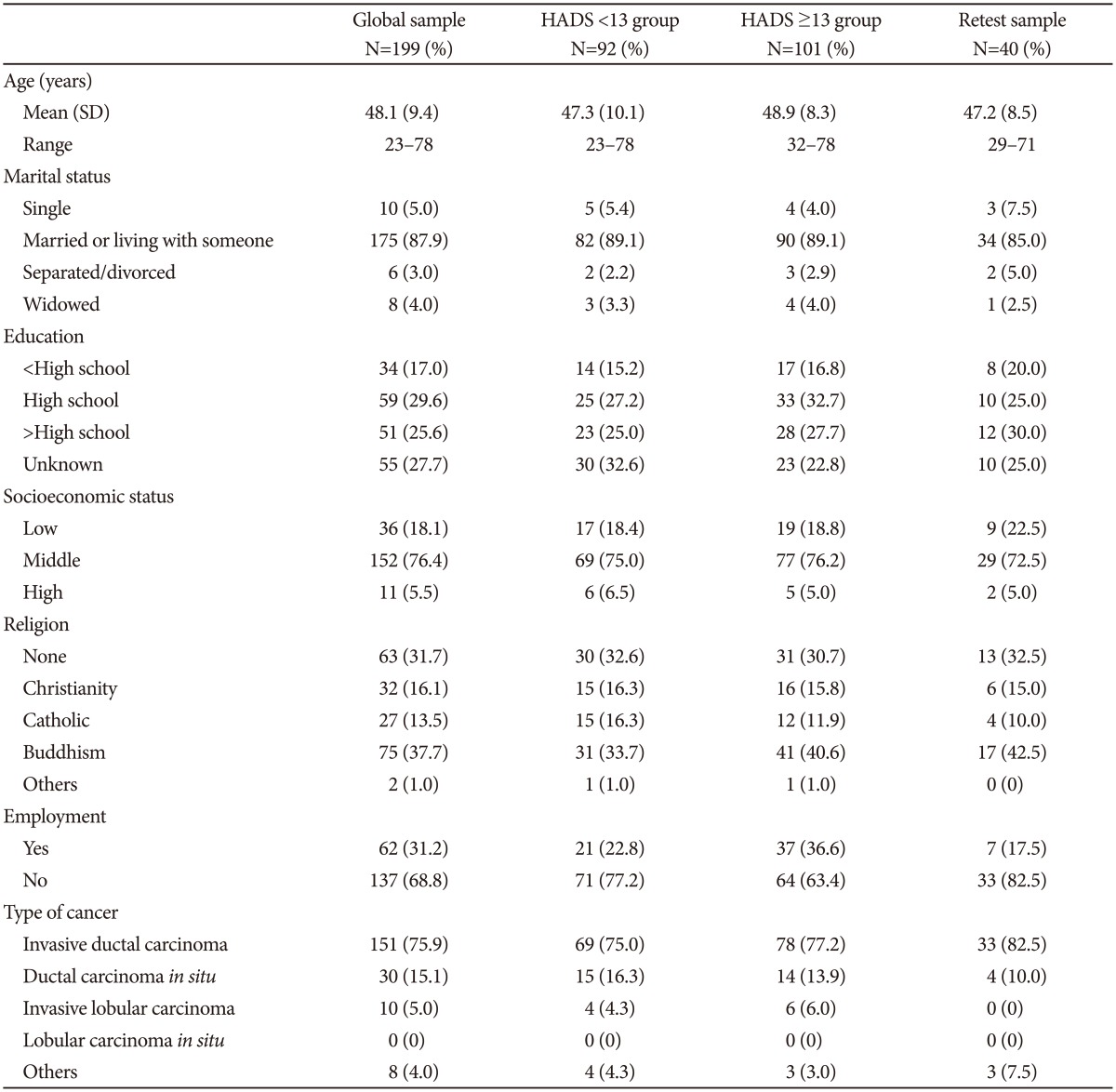

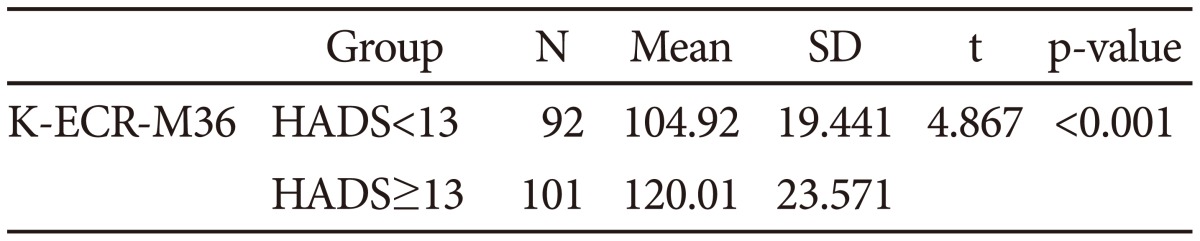

To further analyze the construct validity of the K-ECR-M36, subjects were divided into the two groups: one with a high score of HADS (≥13) and the other with a low score of HADS (<13). HADS is composed of two subscales. According to the developers of HADS, a score (each subscale) of 0-7 should be considered as normal, 8-10 indicates borderline abnormal, 11-21 indicates abnormal. A score of 14 is considered the upper normal limit for total scale; A score of at least 15 should be considered as "abnormal." However, we applied Singer's norm of cutoff score of 13 to the study since our study was focused on cancer patients: The purpose of Singer's study was to determine optimal cutoff scores for the HADS when used in evaluating cancer patients in acute care.20

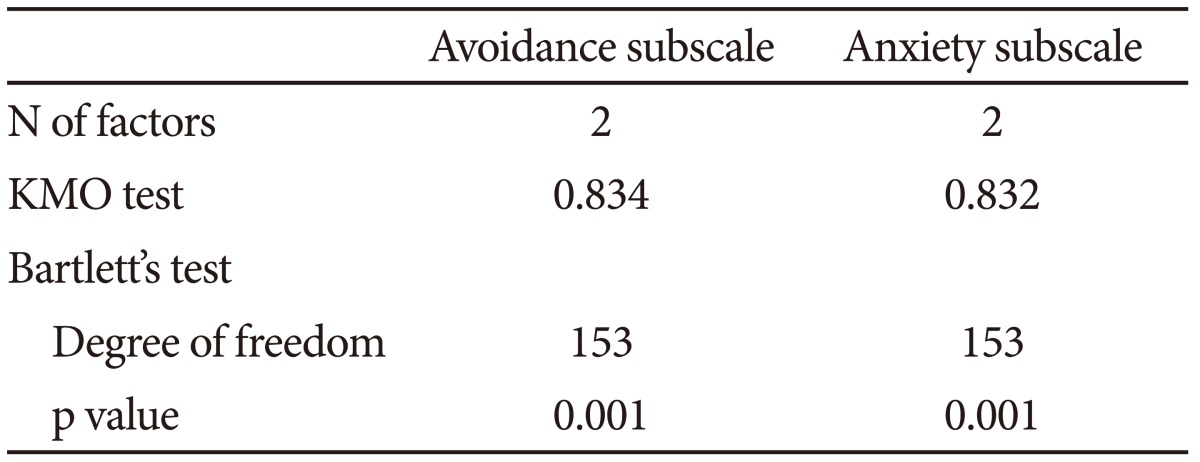

Finally, we conducted a factor analyses using rotated component analysis factor matrix (VARIMAX, SPSS 18.0) on the global sample and on the component subscales, the anxiety and avoidance subscales to evaluate the fit of these models to the data. To define if the subscales were suitable for factor analysis, two statistical tests were used. The first is the Bartlett's test of sphericity, in which it is examined if the subscales of the scale are inter-independent, and the latter is the Kaiser-Meyer Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy. A significant Bartlett's test indicates that there are some relationships between the variables we hope to yield some factors while a KMO value close to 1 indicates that patterns of correlations are relatively compact and so factor analysis should yield distinct and reliable factors.

All statistical analysis was conducted using PASW Statistics for Windows, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical tests were two-tailed.

The demographic data of the 199 patients group were shown in Table 1. Those subjects were further divided into two groups based on HADS scores: high (≥13) and low-score (<13) groups. Among the 199 patients, 193 subjects fully completed the HADS scale. 40 patients of the retest group were also included. The most of woman were diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma (n=151, 75.9%) and the average [standard deviation (SD)] of participants was 48.1 (9.4) years of age. The youngest patient was 23 years old; the oldest patient was 78 years old. Socioeconomic status was measured by participants' own subjective evaluation.

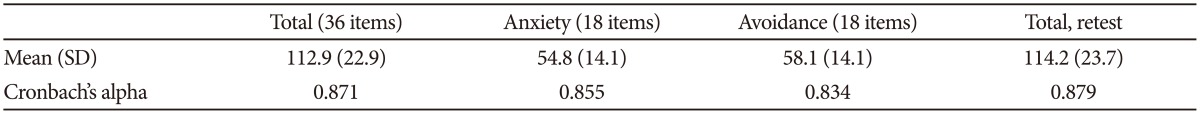

Cronbach's α value showed that the K-ECR-M36 had a reasonable internal consistency in the total 36 items (0.871) as well as in the 18-item subscale of anxiety (0.855) and avoidance (0.834) (Table 2). These coefficients were within the optimal range for this value and consistent with the Cronbach's α of 0.91 for the total items from the original ECR-M36 study. For the 40 participants who finalized the K-ECR-M36 on two occasions with a 6-months interval, the test-retest reliability was conducted by Pearson's correlation analysis (r=0.752, p<0.001; Cronbach's α at retest=0.879).

Construct validity was evaluated by correlation between K-ECR-M36 and other measures (RAAS, HADS and WHOQOL-BREF). A comparison between K-ECR-M36 and two HADS groups were also conducted.

The total score of the K-ECR-M36 was negatively correlated with the total score of the RAAS (r=-0.396, p<0.001); it was correlated negatively with the subscale of dependence plus closeness (r=-0.619, p<0.001) and positively with the anxiety subscale (r=0.493, p<0.001). The K-ECR-M36 was correlated with the HADS positively (HAD-A: r=0.285, p<0.001, HAD-D: r=0.341, p<0.001) and with overall QOL score negatively (r=-0.400, p<0.001).

We hypothesized the group with a lower HADS score would be more emotionally stable and have more secure attachment than the other group. As we expected, the t-test revealed that mean (±SD) score of the K-ECR-M36 in the low HADS group (n=92) was significantly lower than that in the high HADS group (n=101) (104.9±104.9) was significant (t=4.87, p<0.001) (Table 3).

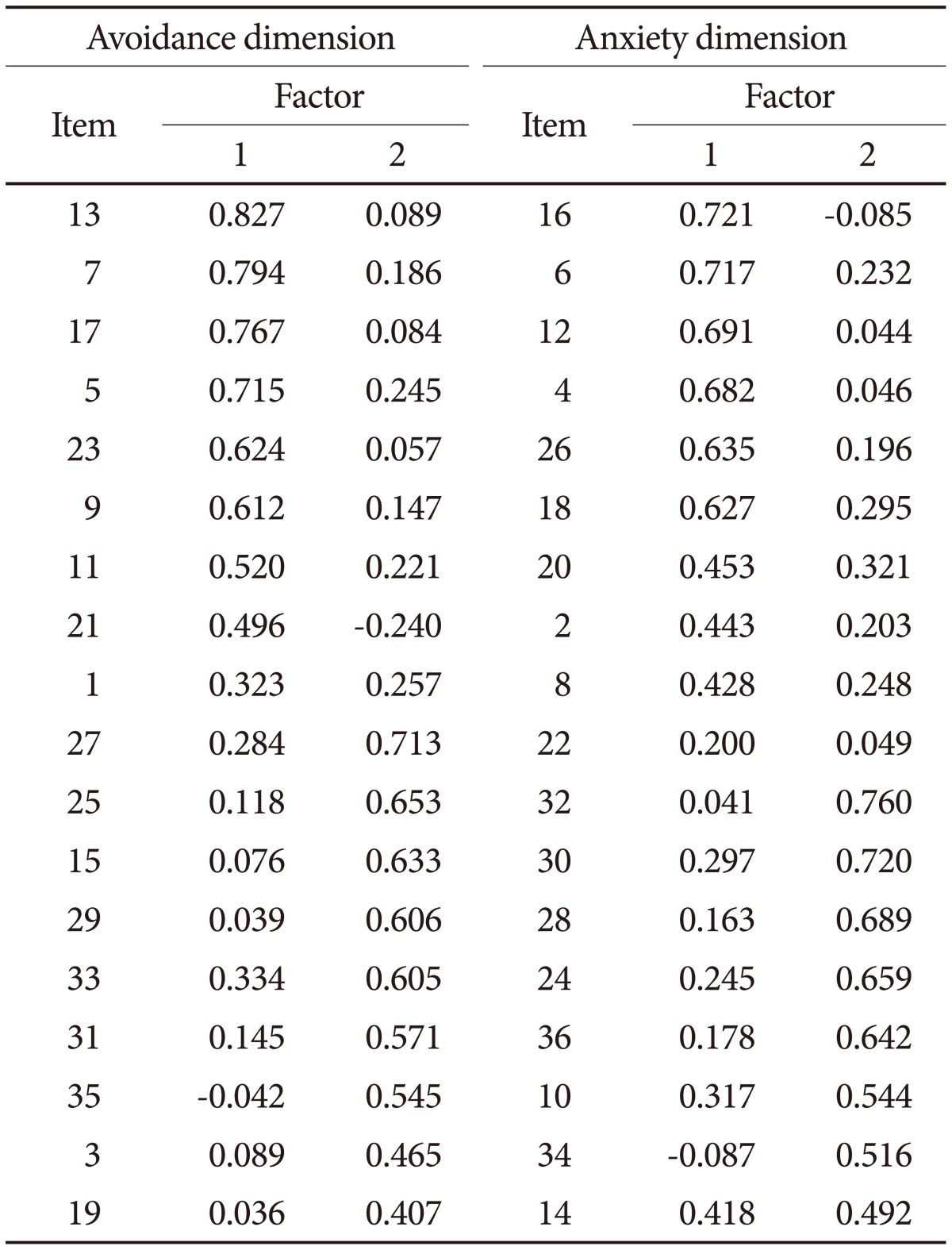

Four correlated factors were initially extracted by exploratory factor analysis of the 36 items, based on the eigenvalue>1 criterion and scree plot examination from the original article of the ECR-M36. They also conducted confirmatory factor analysis and the four factors were extracted (Worrying about Relationships, Frustration about Unavailability, Discomfort with Closeness and Turning Away from Others).

We also conducted an exploratory factor analysis using a rotated component analysis factor matrix (VARIMAX, SPSS 18.0). The KMO-Bartlett test shows that our data is appropriate for factor analysis (Table 4) The rotated component analysis factor matrix is presented in Table 5. Factor analysis resulted in a total extraction of four factors: The anxiety subscales were operationalized into mistrust and frustration; the avoidance subscales were operationalized into closeness and rely on others. The result was similar with that reported in the original article: items 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 18, 20, 22, and 26 for 'mistrust'; items 10, 14, 24, 28, 30, 32, 34, and 36 for 'frustration'; items 1, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, 21, and 23 for 'closeness' and items 3, 15, 19, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, and 35 for 'rely on others'.

Factor 1 was labeled as "mistrust," and consisted of a subset of anxiety items about relational worries. We posited that mistrust is the underlying concept for these worries (e.g., discomfort, separation, rejection and burden). Factor 2 was labeled as "frustration" because items are about the anxious experience of frustration when others are not available. Factor 3 was labeled "closeness" because its items are directly related to intimacy and comfort about others. Finally, factor 4 consisted of avoidance items and was labeled "rely on others" because the component items are about the dependence and reliance.

Recently, the area of research for adult attachment has extended from psychiatric disorder to medical conditions such as chronic pain and cancer.2122232425 These studies showed the importance of attachment insecurity for depression and the role of attachment style for adjustment and coping in medical circumstances such as cancer and chronic pain.621 Meredith et al.6 found that attachment insecurity might be a risk factor for depression those who have chronic pain. Several studies found the evidences that insecure attachment is associated with poorer functioning and in cancer patients and their caregivers.222325 In this context, it might be essential to evaluate and understand the attachment style for medically ill individuals.

Through the current study, we found that the K-ECR-M36 showed good reliability and validity. Construct validity was also supported by the positive associations of depression and anxiety score (HADS) with the K-ECR-M36 attachment scale. Two subscales of the K-ECR-M36 were negatively or positively correlated with the RAAS depending on subscales. Moreover all of the domains of the WHOQOL-BREF was negatively correlated with the K-ECR-M36 (r=-0.400, p<0.001).

K-ECR-M36 was further assessed by comparing the two groups. We assumed that low scores of HADS group (HADS<13) would have a secure attachment score. The results were largely consistent with our predictions. T-test showed a statistically reasonable difference between the groups. We tried to divide other groups regarding their cancer stage and Body image scale to obtain if there are differences in the attachment score. As we expected, there were no statistically reasonable differences between the groups.

Finally, we used factor analysis on the scales above. The authors extracted two factors for each subscale. Most items were divided similarly to the original article except for some items. Items 18, 26, 30, 36 were allocated into a group of frustration about unavailability in the original article. However, item 18 and 26 were categorized into of mistrust, while item 30 and 36 were categorized into a group of frustration for the study. Mistrust and frustration are reciprocal relationships. In other words, mistrust could cause a frustrated feeling in personal relations; the opposite relationship is also possible. For this reason, some items of factor 'mistrust', 'frustration' could be complementary.

There was one study tried to know the mode for adjustment of couple in lung cancer.21 Interestingly, the mode of adaptation was different to a considerable degree depending on attachment style: overall the adaptation was poorer in avoidant patients. K-ECR-M36 has two separate subscales and can be divided into smaller subscales as mentioned above, so it can be used for complex-designed researches to find results depending on specific attachment style. On the other hand, total score system of K-ECR-M36 can be used in relatively simple designed studies or for researchers who are not experienced attachment theory.

Overall, the results indicated that the K-ECR-M36 displayed suitable construct validity as a measure of attachment representations of breast cancer patients.

Our study had several limitations as well as strengths. A clear strength is that we examined the variety of scale from recently diagnosed hospital based breast cancer patients.

The current findings should be cautiously interpreted considering the followings. First of all, the high number of patients relinquishes a retest follow up study. A further longitudinal study is needed to examine the test-retest reliability of the K-ECR-M36 in a larger sample than the presented 40 retest participants.

Secondly, the study participants were not gathered from the general cancer populations and breast cancer patients were incorporated only. Future research is also required to confirm the psychometric properties of the K-ECR-M36 in other cancer populations and medically ill patients. However, we believe that this scale could be used not only for breast cancer patients but also other disease group since the scale does not include disease specific questions. Attachment representations manifest themselves in belief-systems and styles of emotional responding and in motivated action. Specifically secure attachment is not only essential for the self-control in breast cancer patients but also in other chronic ill patients.

In terms of clinical implication on this measure, it is important to be aware that the attachment style reflects a tendency of patients to respond in a certain way and that the interaction within a specific relationship influences feelings and behavior. Thus, the role of the physician and close people is highly important in shaping the relationship and enhancing and maintaining feelings of trust and satisfaction in insecurely attached patients. An important next step is to make this knowledge available and practically useful for physicians and close people since the adjustment process is not a single unitary concept, but rather a chain of dealing with various tasks.

In conclusion, we found the K-ECR-M36 to have an established factor structure and an acceptable internal consistency, test-retest reliability and construct validity across the samples of the examined breast cancer patients. K-ECR-M36 could be used as a practical tool to evaluate the attachment concern on a sample of breast cancer and medically ill patients. Further studies are needed to fully evaluate the K-ECR-M36, including its application to other cancer populations and medically ill people knowing the attachment style can be a powerful tool in cultivating a more understanding relationship between the people and help to develop fare well, find fulfillment and cultivate enduring happiness even in a disaster situation.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://dx.doi.org/10.4306/pi.2015.12.4.483.

References

1. Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. New York: Basic Books; 1969.

2. Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. Separation: Anxiety and Anger. New York: Basic Books; 1973.

3. Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall SN. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1978.

4. Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987;52:511PMID: 3572722.

5. Naaman S, Radwan K, Johnson S. Coping with early breast cancer: couple adjustment processes and couple-based intervention. Psychiatry 2009;72:321-345. PMID: 20070132.

6. Meredith PJ, Strong J, Feeney JA. Adult attachment variables predict depression before and after treatment for chronic pain. Eur J Pain 2007;11:164-170. PMID: 16517191.

7. Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Pereg D. Attachment theory and affect regulation: the dynamic development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motiv Emot 2003;27:77-102.

8. Simpson JA, Rholes WS. Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. In: Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR, editor. Self-Report Measurement of Adult Attachment. New York: The Guilford Press, 1998, p. 46-76.

9. Lo C, Walsh A, Mikulincer M, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Measuring attachment security in patients with advanced cancer: psychometric properties of a modified and brief Experiences in Close Relationships scale. Psychooncology 2009;18:490-499. PMID: 18821528.

10. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in 2010. Cancer Res Treat 2013;45:1-14. PMID: 23613665.

11. Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Lee JY, Seo HG, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2009. Cancer Res Treat 2012;44:11-24. PMID: 22500156.

12. Boyle P, Howell A. The globalisation of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2010;12(Suppl 4):S7PMID: 21172091.

13. Khang D, Rim HD, Woo J. The Korean version of the body image scale-reliability and validity in a sample of breast cancer patients. Psychiatry Investig 2013;10:26-33.

14. Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J Pers Soc Psychol 1990;58:644-663. PMID: 14570079.

15. Collins NL. Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;71:810-832. PMID: 8888604.

16. Kim EJ, Kwon JH. Interpersonal characteristics related with depressive symptoms: focused on adult attachment. Korean J Clin Psychol 1998;17:139-153.

17. Snaith RP, Zigmond AS. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:344

18. Oh SM, Min KJ, Park DB. A study on the standardization of the hospital anxiety and depression scale for Koreans: a comparison of normal, depressed and anxious groups. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 1999;38:289-296.

19. Min SK, Lee CI, Kim KI, Suh SY, Kim DK. Development of Korean version of WHO quality of life scale abbreviated version (WHOQOL-BREF). J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 2000;39:571-579.

20. Singer S, Kuhnt S, Götze H, Hauss J, Hinz A, Liebmann A, et al. Hospital anxiety and depression scale cutoff scores for cancer patients in acute care. Br J Cancer 2009;100:908-912. PMID: 19240713.

21. Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Davis D, Rumble M, Scipio C, Garst J. Attachment styles in patients with lung cancer and their spouses: associations with patient and spouse adjustment. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2459-2466. PMID: 22246596.

22. Hunter MJ, Davis PJ, Tunstall JR. The influence of attachment and emotional support in end-stage cancer. Psychooncology 2006;15:431-444. PMID: 16155969.

23. McLean LM, Walton T, Matthew A, Jones JM. Examination of couples' attachment security in relation to depression and hopelessness in maritally distressed patients facing end-stage cancer and their spouse caregivers: a buffer or facilitator of psychosocial distress? Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1539-1548. PMID: 20798960.

24. Ciechanowski P, Sullivan M, Jensen M, Romano J, Summers H. The relationship of attachment style to depression, catastrophizing and health care utilization in patients with chronic pain. Pain 2003;104:627-637. PMID: 12927635.

25. Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Rodin G. Hidden morbidity in cancer: spouse caregivers. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4829-4834. PMID: 17947732.