|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 10(4); 2013 > Article |

Abstract

Objective

This study examined the reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Child Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI) in Korean children aged from 6 to 12 years old and the suitability of and potential for clinical application of the CSBI in Korean population.

Methods

The participants consisted of 158 typically growing children and 122 sexually abused children. The subjects were evaluated using the Korean version of the Child Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI), the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), and the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children (TSCYC). Internal consistency was examined as a measure of reliability. To investigate the concurrent validity, Pearson's correlations were calculated. One-way ANCOVA was used to demonstrate discriminant validity.

Results

The Cronbach's α value was 0.84. The CSBI total score was moderately correlated with the CBCL subscales and mildly correlated with the sexual concern subscale of the TSCYC. The total score of the CSBI for the sexually abused children group was significantly higher than that of typically growing children group.

Sexual abuse includes a spectrum of activities ranging from rape to physically less intrusive sexual abuse.1,2 Child sexual abuse has been a topic of public and governmental investigation for the past few years in Korea because of the notorious child sexual abuse victim case called the 'Cho Doo-Sun case' named after the assaulter in 2008. Since then Koreans have become more concerned about child sexual abuse, the issue has come under public scrutiny, and the Korean National Statistical Office reported more than 1,017 child sexual abuse cases among children under 13 years old in 2009. Sexually abused children shows sexual behavior problems and other generic behavior problems3,4 and are prone to psychiatric disorders such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, dissociative disorder, and so forth as a result.5 Sexually abused children as a group exhibit more sexual behavior problems than non-sexually abused children.6-8 Because of incomplete cognitive and language development, young children are not able to disclose sexual abuse, and caretakers must have knowledge of the symptoms of child sexual abuse to recognize the abuse as early as possible and provide them with more appropriate help. Therefore mental health professionals have developed and used standardized assessment measures as a need of accurate evaluating the symptoms of child sexual abuse. There are several instruments designed specifically for children and adolescents who are suspected of having been or being currently sexually abused, which are the Anatomical Doll Questionnaire (ADQ), the Checklist of Sexual Abuse and Related Stressors (C-SARS), and the Child Sexual Behavior inventory (CSBI), Negative Appraisals of Sexual Abuse Scales (NASAS), and Sexual Abuse Fear Evaluation (SAFE).9-11 The ADQ is semi-structured 2-7 years old child interview by the use of anatomical dolls (other than verbal format). It is purposed to find out type of abuse, to observe child's behaviors and perceptions of interview quality. The C-SARS is self-report, assessing both reports and degree of stressful events associated with a sexual abuse. The CSBI assesses a wide range of sexual behavior that covers a number of domains including boundary problems, exhibitionism, gender role behavior, self-stimulation, sexual anxiety, sexual interest, sexual intrusiveness, sexual knowledge, and voyeuristic behavior by caregiver. The NASAS measures perception of threat of harm associated with sexual abuse. The SAFE assesses abuse-related fear. There are other measures evaluating children's behavior by caregiver, which are Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children (TSCYC). However these are not for specific subject who are sexually abused children. The CSBI was developed following research that identified the sexual items on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) developed by Achenbach et al.12 The CSBI was developed by Friedrich in 1991. Two other versions have been developed since the first version of the CSBI.13 The CSBI has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity.13,14 Koreans has been directly influenced by Confucianism since the Chosun dynasty (14th-19th centuries) and the word 'sexual' has been a taboo, and which has impeded the inquiries in children's experiences of sexual abuse directly and even indirectly. Even if external evidence of abuse such as gonorrhea had existed, disclosure rates among children have been less than 50%.15 As a result, recent research on the consequences of sexual abuse has focused on the need for a more systematic examination,9 especially by caretakers. The CSBI has advantages of sexual abuse-specific measure and being useful for evaluating sexual behavior of children who have been sexually abused or suspected of having been sexually abused.16 Until now, little research for measuring child sexual behavior after sexual abuse has been carried out in Korean society.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Child Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI) in Korean children aged from 6 to 12 years old and the suitability of and potential for clinical application of the CSBI in a Korean population.

The questionnaire was administered to caretakers of 168 children aged from 6 to 12 years old who were attending one kindergarten and one elementary school in Daegu, a city in southeastern South Korea with approximately 2.5 million habitants. Permission was obtained in advance from the headmaster and teacher and parents' committee of the school board of the school in which the study was performed. The Ethics Committee of Kyungpook National University Hospital granted permission for the study. Participants were not compensated. A total of 168 caretakers of children agreed to participate in the study, and children with mental retardation or prior psychiatric diagnosis and treatment were excluded. The response rate was 94.04% giving a sample of 158 children. The final sample included 66 boys and 92 girls. The mean age in the typically growing children (TG) group was 9.47 years old (SD=1.72); boys only, 9.61 (SD=1.61) and girls only, 9.39 (SD=1.80). We also investigated the demographic data including parental education level and economic status. One case of paternal education, eleven cases of maternal education and two cases of economic status were missed by the informants.

The sexually abused children (SA) group consisted of 122 children (32 boys and 90 girls) with a confirmed history of sexual abuse, who had visited the Daegu Sunflower Center, the treatment center for sexually traumatized children in Daegu. Parents or another main caretaker gave informed consent for participation. In each case, sexual abuse was confirmed by clinical evaluation by child and adolescent psychiatrists and forensic nurses, the child's statements, perpetrator confession, medical evidence, and/or eyewitness testimony. The mean age in the SA group was 9.11 years old (SD=2.04); boys only 9.05 (SD=2.55) and girls only 7.83 (SD=2.71). We also gathered demographic data concerning the participants' parental educational level and family socioeconomic status. Missing data of these items were 37 of paternal education, 36 of maternal education and 36 of socioeconomic status. We investigated sexual abuse characteristics of the participants. The characteristics are the route of Daegu Sunflower Center visit, age of perpetrator, relationship with perpetrator, duration of sexual abuse, time elapse from last abuse to center visit, and whether penile penetration was existed.

The Child Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI) is the tool which utilizes the parent's report of sexual behavior in children aged from 2 to 12 years. It presents the primary caregiver with a list of behaviors the parent has observed in the prior 6 months. The full version of the CSBI consists of 38 items and each item is rated on a 4-point scale anchored at 0 (never) and 3 (at least once per week) and requires a fifth grade reading level.15 Item 38 is a question which asks the respondent to directly describe "other sexual behavior" and is scored ranging from 0 to 3 according to its frequency. The CSBI requires 5 to 8 minutes for most caregivers to complete or up to 15 minutes if the items are read to the caregiver as an interview.17 The first 35-item version of the CSBI (i.e., CSBI-1) was developed in 1991 and the second version of the CSBI (CSBI-2) developed in 1993 by Friedrich et al.14 consists of 36-items. Both the CSBI-1 and CSBI-2 have demonstrated good reliability and validity.17 The third and last version of the CSBI (CSBI-3) is a 38-item questionnaire containing 22 of the CSBI-2 items reworded for easier readability and greater clarity, and it was formally published in 1997 by Psychological Assessment Resources. The CSBI-3 had been examined for its reliability and validity by Friedrich et al.14 in 2001. The alpha coefficient of the CSBI-3 was 0.72 for the normative sample and 0.92 for the sexual abuse sample. Discriminant validity was proven by the higher scores in sexually abused children than non-sexually abused children and concurrent validity was demonstrated by showing the correlation of the CSBI and another scale for checking children's behavior.14 Norms in the CSBI-3 were calculated for 2- to 5-years, 6- to 9-years, and 10- to 12-years because the item mean scores were markedly different according to three different age groups.19 The second version of the CSBI had been translated into Korean by Psychologist ChoongRai Nho and it had been published as an appendix to his book, "The Understanding of Child Sexual Abuse" in Korea. However, we could not find any peer reviewed paper on this Korean version of the CSBI or obtain data on the validity and reliability of the instrument. Therefore, a psychiatrist in our department translated the third and latest 38-item version of the CSBI into the Korean language with the goal of verifying the reliability and validity of the new Korean version. The Korean version was back-translated into English and the original version and back-translated version were compared for meaning.

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was used for the purpose of testing the concurrent validity of the CSBI. The CBCL is a widely used 113-item behavior rating scale for children ages 4-18 years old.20,21 Each item is rated on a 3 point scale anchored at 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat true) and 2 (often true). The CBCL divides children's behavior problems into internalizing problems and externalizing problems. Internalizing problems include withdrawn, somatic concerns, anxious/depressed. Externalizing problems include aggression and delinquency. Before the development of the first version of the CSBI in 1983, six sexual behavior items on the CBCL17 were useful in discriminating sexually abused from children without sexual abuse.22 The Korean version of the CBCL was developed and has been widely used as a screening tool for behavioral problems of children.23 The CBCL was answered by all participants of the TG group and 92 participants of the SA group.

Descriptives were obtained for the demographic data. Sample differences of demographic data were examined by basic bivariate analysis, applying the t-test and the chi-squared test. The values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. The extent to which items on the Korean version of the CSBI are internally consistent was assessed using Cronbach's alpha. A standard of 0.90 or higher was considered excellent.24 To assess internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha values when the item was deleted were also calculated.

To investigate the concurrent validity between the Korean version of the CSBI and other caregiver scoring scales that evaluate a child's behavior, Pearson's correlations between the CSBI and CBCL were calculated. One-way ANCOVA was used to demonstrate discriminant validity of the Korean version of the CSBI between the TG group and SA group with the covariates of sex, parental educational status, and economic status. Discriminant validity was determined on the basis of differences between the item means for 38 individual CSBI items and the total score between the two groups. A series of ANCOVAs using the CSBI total score was performed separately for boys and girls, and for two age groups, 6 to 9 years, and 10 to 12 years old. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS for Windows (version 18.0). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kyungpook National University Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent after the study had been fully explained.

An analysis of demographic data describing the two samples is given in Table 1. The sample size of the typically growing children (TG) group consisted of 66 boys and 92 girls, and that of the sexually abused children (SA) group was 32 boys and 90 girls. We investigated the demographic data such as parental education level and economic status by Hollingshead et al.25 Age was not significantly different between the two groups. The female ratio was significantly higher in the SA group (χ2=7.31, p=0.01). Educational status of the parents (Father χ2=69.93, p<0.001, Mother χ2=63.23, p<0.001) and economic status (χ2=77.97, p<0.001) were significantly lower in SA group than in TG children group. We also investigated sexual abuse characteristics of SA group participants.

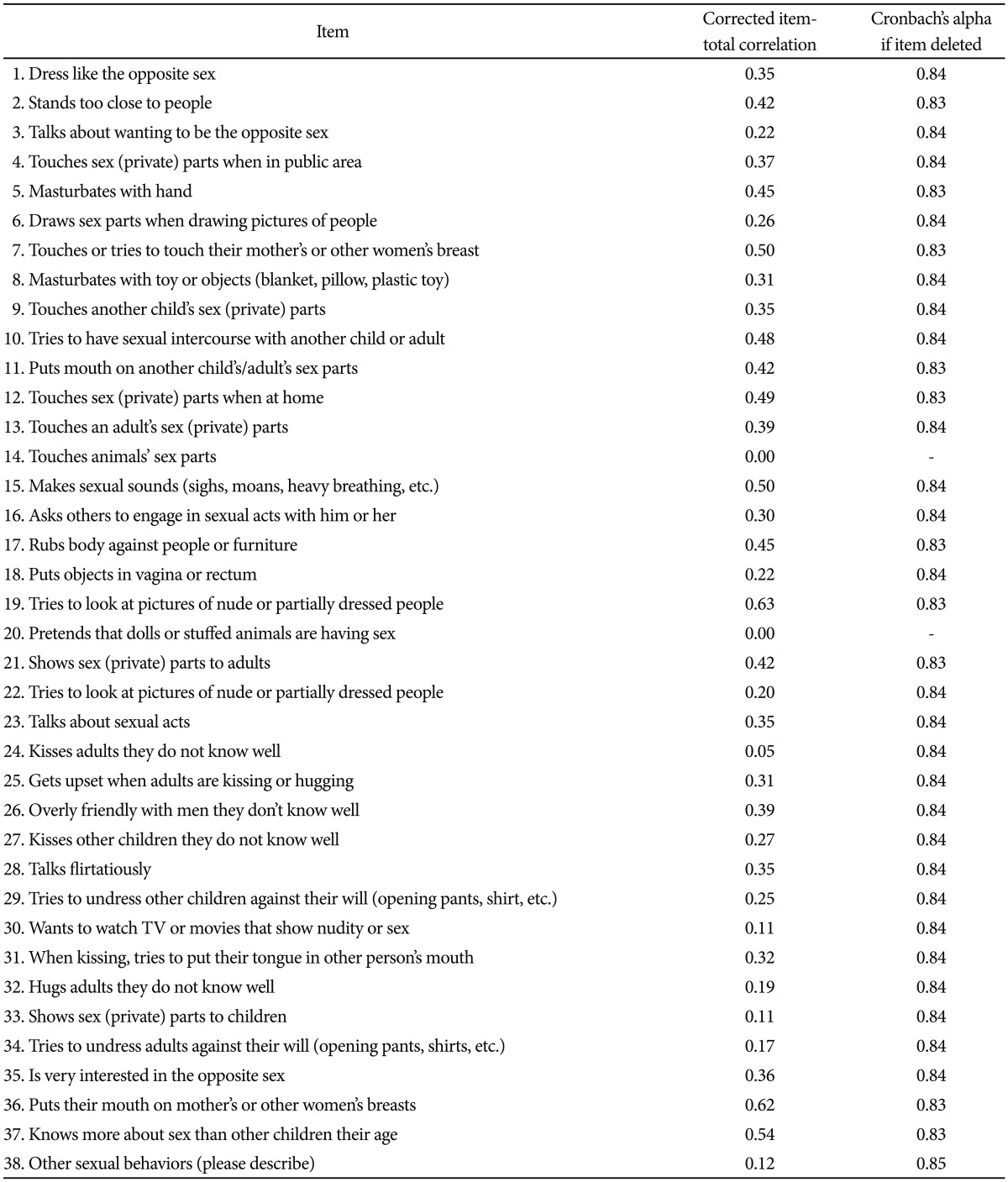

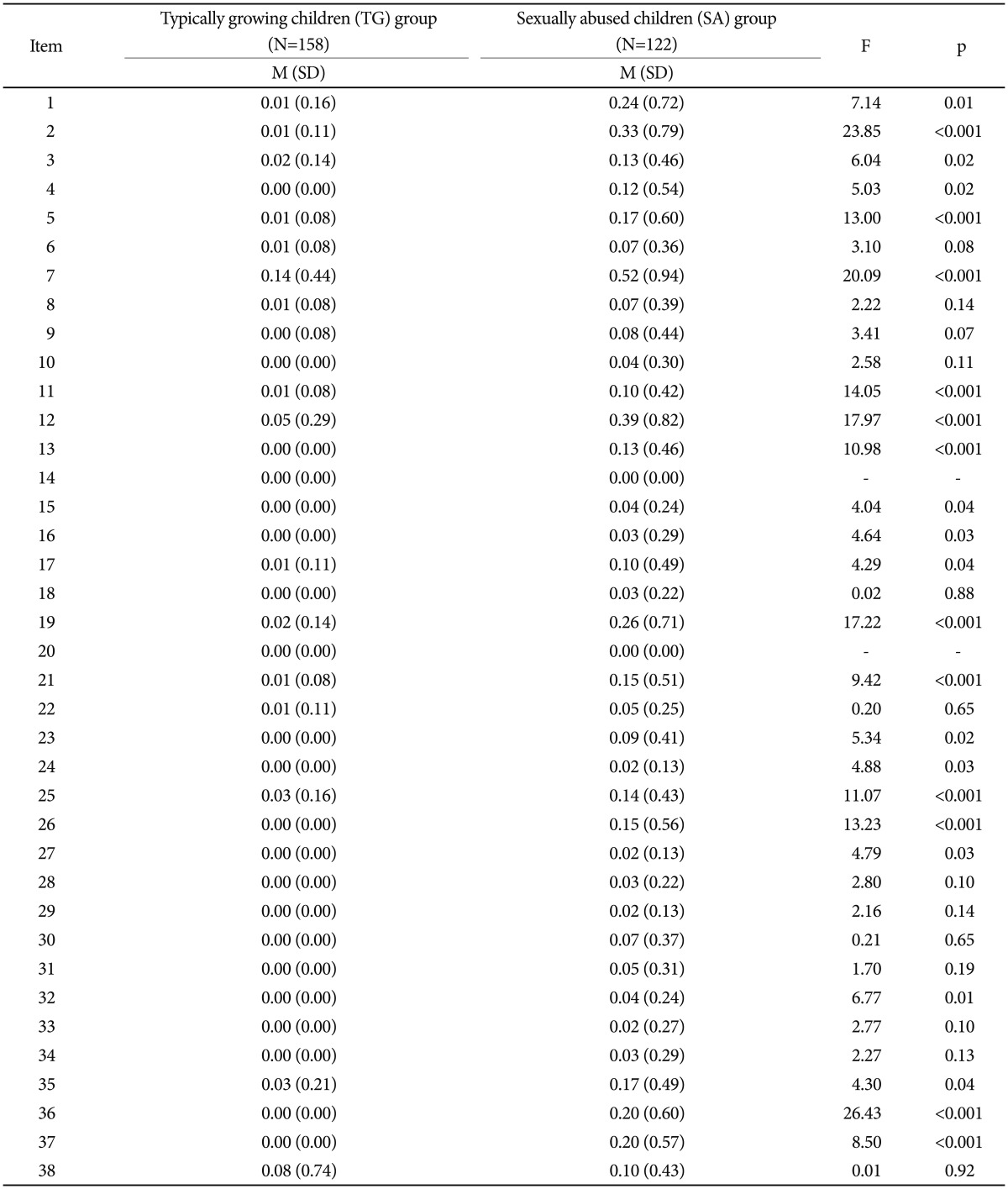

The internal consistency for the CSBI was measured by Cronbach's alpha. Item 14 and item 20 were excluded for analysis because all of the participants reported '0' points for these two items. The alpha coefficient was 0.47 for 158 participants of TG group and 0.83 for 122 participants of SA group. The resulting alpha coefficient for the total 280 participants sample was 0.84, indicating good internal reliability of the Korean version of the CSBI. The alpha value increased to 0.85 when item 38 was deleted. All of the other items did not increase the Cronbach's alpha when removed (Table 2).

The inter-scale correlation was calculated. The correlation of the CSBI and the CBCL for 250 samples was examined with the Pearson product-moment correlations. The CSBI total score was moderately correlated with the total problematic behaviors scale of the CBCL (r=0.43, p<0.001). It was significantly correlated with the internalizing problems scale of the CBCL (r=0.40, p<0.001) and with the externalizing problems scale of the CBCL (r=0.38, p<0.001). In addition, the CSBI total score was negatively correlated with the total competence subscale of the CBCL (r=-0.15, p=0.02) and school competence subscale of the CBCL (r=-0.20, p=0.02) (Table 3).

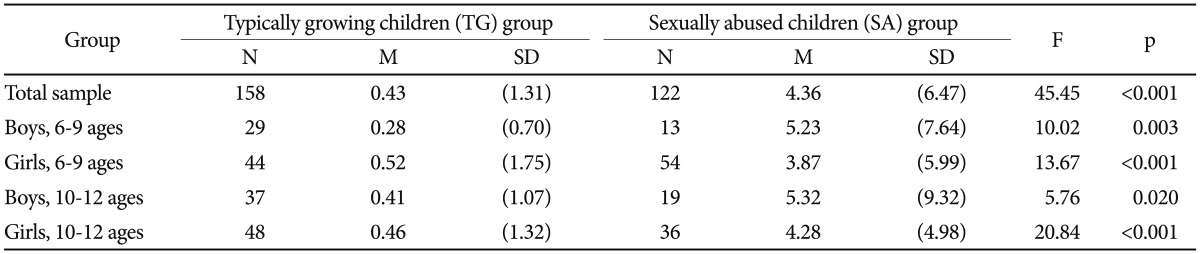

The total score of the CSBI for the SA group (n=122) was significantly higher (4.36±6.47) than in the TG group (n=158) (0.43±1.31), adjusting for sex, parental educational status, and economic status. The CSBI total score of the boys was significantly higher in the SA group than it was in the TG group, in both the 6 to 9 years old group (5.23±7.64 vs. 0.28±0.70; p=0.003) and 10 to 12 years old group (5.32±9.32 vs. 0.41±1.07; p=0.020). The CSBI total score of the girls was also significantly higher in the SA group than it was in the TG group, in both the 6 to 9 years old group (3.87±5.99 vs. 0.52±1.75; p<0.001) and 10 to 12 years old group (4.28±4.98 vs. 0.46±1.32; p<0.001) (Table 4). When the mean score of each item was compared between the two groups, that of thirteen items (item 6, 8, 9, 10, 18, 22, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, and 38) was not significantly different. Item 14 and item 20 were excluded for analysis because all of the participants in both groups reported a '0' score. The mean scores of the remaining 23 items were significantly different between the two groups (Table 5).

This study examined a range of sexual behaviors measured by the Korean version of the Child Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI) in a sample of Korean children aged 6 to 12 years old. The CSBI is specific measure for sexually abused children and has advantages of evaluating children who are incomplete in terms of cognition and language development because it is reported by caregiver. The purpose of this study was to examine the psychometric properties including the reliability and validity of the tool, and to evaluate the possibility of clinical application of the Korean version of the CSBI in Korean society.

There was a higher non-response rate on the demographic data in the sexually abused children (SA) group (maternal educational level 29.5%, paternal educational level 30.4%, economic status 29.5%) than the typically growing children (TG) group (maternal educational level 7.0%, paternal educational level 0.6%, economic status 1.3%). The economic status in the SA group was lower than was that of the TG group. The parental education level was also lower in the SA group than in the TG group.

The author of the English version of the CSBI reported that the alpha coefficient of that version of CSBI was 0.72 for the normative sample and 0.92 for the sexual abuse sample.14 The alpha coefficient was higher in the SA group than the TG group in both our study and the original study.14 This indicates that the Korean version of the CSBI, like the original scale, is more reliable measurement for children with sexual abuse.

In the TG group, the alpha coefficient was low as 0.47 because 16 items all with a score of '0' were excluded from the calculations. In explaining the large number of '0' answers, we must take into consideration the conservative Korean culture based on Confucian strictures including sexual taboos even among the adults, which likely affected the parents' ability to observe and report their children's sexual behavior. Because the CSBI was designed to detect problematic sexual behavior earlier among sexually abused children, the Cronbach's alpha value for the SA group of 0.83 and that of 0.84 for all of the participants taken together showed the good reliability of this scale. If item 38 was deleted, the Cronbach's alpha value increased to 0.85. Item 38 is an essay question, and a number of participants did not fill out this item. This was likely to have contributed to the elevation of Cronbach's alpha when item 38 was deleted. The degree of the increase is so slight that item 38 did not need to be excluded.

Sexually abused children had higher scores than nonabused children in the sex problems subscale of the CBCL in previous studies; however, the sex problems subscale scores of the CBCL were not significantly different between the two groups.22,26,27 The sex problems subscale of the CBCL consists of only 6 items28 and it does not discriminate the problematic sexual behavior from other problematic behavior in the sexually abused children, which implies that the CSBI, more reliable and valid instrument, is strongly necessary in Korean culture. In our study, the total score of the CSBI was more strongly correlated with the total problematic behavior (r=0.43) and internalizing problems (r=0.40) subscales rather than the sex problems (r=0.27) and externalizing problem (r=0.38) subscales. However, in the study of Friedrich et al., the CSBI total score showed stronger correlation with the CBCL's externalizing problems subscale (normative group r=0.43, sexual abuse group r=0.47) than the internalizing problems subscale (normative group r=0.35, sexual abuse group r=0.36).

Significant group differences of in gender, parental educational level, and economic status were identified both in our study and the study of the original author.14 Our finding that the CSBI total score was significantly higher in the SA group than the TG group not only for the total sample but also for the two age groups (6 to 9 and 10 to 12-years old) considered separately according to developmental stage accords with the study of the original author.

In this study, the mean total score of the CSBI was lower than that of the original author's study, not only in TG group (0.43±1.31 vs. 3.7±4.5), but also in SA group (4.36±6.47 vs. 13.5±15.2).14 These results reflect the characteristic of Korean society that people generally want to provide socially desirable answers, even more than in Western society. More '0' scores on more items also lowered the total score. These results corresponded with previous studies showing that in Korean society people generally want to provide socially desirable answers, even more than in Western society.30

Comparisons of all 38 items of the CSBI between the two groups were also examined. Friedrich et al.14 found that all 38 items of the CSBI were endorsed significantly more often (p<0.05) for the sexually abused children samples than for the normative samples. The present study revealed that some items (item 6, 8, 9, 10, 18, 22, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, and 38) of the CSBI did not differ significantly across the two groups. It cannot be completely ruled out that Korean children show fewer sexual behaviors after sexual abuse than Western children. Another explanation might be a cultural difference between Eastern and Western countries. Cho et al.29 suggested that the stigma for mentally ill patients was so severe in Korea that many of the respondents had a tendency to conceal their symptoms.30 This interpretation is supported by the finding that the means of the CSBI total score of not only SA group but also TG group in our study are lower than those of previous studies with Western samples. Taylor et al.31 explained that Korea is one of the countries in which subjects show a response bias because they want to give an answer as socially desirable as possible. Thus the nuance or meaning of words used in the CSBI scale concerning sexual behavior could repulse Korean participants. However, most sexual behaviors indicated by these items have been regarded as important in child and adolescent psychiatry.32,33 Therefore, although there were no significant group differences for these individual items, they still have clinical value, and we must apply the results of all of the items to effectively evaluate and treat sexually abused children.

Item 14 and item 20 were scored as '0' by all 280 participants. Item 14 is "Touches animals' sex parts" and item 20 is "Pretends that dolls or stuffed animals are having sex." Most Koreans live in apartments, unlike many Westerns, and apartment dwellers generally prohibited from keeping animals. Thirtynine percent of U.S. households own at least one dog and thirty-three percent of U.S. households own at least on cat, on the other hand, approximately twenty-one percent of Korean households own pets.34,35 Therefore, Korean children tend to have less opportunity to touch animals. However, Item 20 is commonly reported sign of child sexual abuse in Western society, so we need to evaluate more information about this item through large scale research henceforth.

There are limitations to our study. First, in this study, testretest reliability was not examined and a later study should investigate the test-retest reliability of the Korean version of the CSBI to confirm the reliability of this scale with greater accuracy. Second, sample size of this study was quite small in comparison with the study of previous authors.15 We recruited 158 participants for the TG sample and 122 for the SA sample. Third, although the CSBI was developed for measuring sexual behavior in children aged 2 to 12 years, we only evaluated children ranging from 6 to 12 years the analysis of children aged 2 to 5 years old was absent from our study. Fourth, there was selection bias in including only sexually abused children identified to be in need of mental health services. Fifth, the study was not intended to measure the underlying psychiatric disorders of the SA group participants. Previous or comorbid psychiatric disorders may influence sexual behaviors. Sixth, the CSBI scoring system contains Developmentally Related Sexual Behavior (DRSB) and Sexual Abuse Specific Items (SASI) according to gender and age in addition to the CSBI total. We did not examine these two scales. The DRSB and SASI could discriminate among children's various symptoms to distinguish normal developmental sexual behavior and sexual abuse-related behavior. Thus, it is helpful that psychiatrists or practitioners understand a child's age-appropriate sexual behavior.

In conclusion, the Korean version of the Child Sexual Abuse Inventory (CSBI) is reliable and valid, and it can be an appropriate clinical tool for assessing the sexual behavior of Korean children aged from 6 to 12 who are suspected to have been sexually abused.

References

1. Finkelhor D. Child Sexual Abuse. New York: Free Press New York, New Theory and Research; 1984.

2. Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse: a review of the research. Psychol Bull 1986;99:66-77. PMID: 3704036.

3. Alexander KW, Quas JA, Goodman GS, Ghetti S, Edelstein RS, Redlich AD, et al. Traumatic impact predicts long-term memory for documented child sexual abuse. Psychol Sci 2005;16:33-40. PMID: 15660849.

4. Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: a conceptualization. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1985;55:530-541. PMID: 4073225.

5. Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health 2001;91:753-760. PMID: 11344883.

6. Drach KM, Wientzen J, Ricci LR. The diagnostic utility of sexual behvior problems in a forensic child abuse evaluation clinic. Child Abuse Negl 2001;25:489-503. PMID: 11370722.

7. Cosentino CE, Meyer-Bahlburg HF, Alpert JL, Weinberg SL, Gaines R. Sexual behavior problems and psychopathology symptoms in sexullay abused girls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995;34:1033-1042. PMID: 7665442.

9. Friedrich WN. Sexual victimization and sexual behavior in children: a review of recent literature. Child Abuse Negl 1993;17:59-66. PMID: 8435787.

10. Friedrich WN, Grambsch P, Broughton D, Kuiper J, Beilke RL. Normative sexual behavior in children. Pediatrics 1991;88:456-464. PMID: 1881723.

11. Strand VC, Sarmiento TL, Pasquale LE. Assessment and screening tools for trauma in children and dolescents: a review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2005;6:55-78. PMID: 15574673.

12. Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Child Behavior Checklist. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1981.

13. Friedrich WN, Grambsch P, Damon L, Hewitt SK, Koverola C, Lang RA, et al. Child sexual behavior inventory: normative and clinical comparisons. Psychol Assess 1992;4:303-311.

14. Friedrich WN, Fisher JL, Dittner CA, Acton R, Berliner L, Butler J, et al. Child Sexual Behavior Inventory: normative, psychiatric, and sexual abuse comparisons. Child maltreat 2001;6:37-49. PMID: 11217169.

15. Bottoms BL, Najdowski CJ, Goodman GS. Children As Victims, Witnesses, and Offenders. Psychological Science and the Law. New York: The Guilford Press; 2009.

16. Kendall-Tackett KA, Williams LM, Finkelhor D. Impact of sexual abuse on children: a review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychol Bull 1993;113:164-180. PMID: 8426874.

17. Achenbach T. Child Behavior Checklist/4-18. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1991.

18. Friedrich WN, Share MC. The Roberts Apperception Test for children: an exploratory study of its use with sexually abused children. J Child Sex Abus 1998;6:83-91.

19. Friedrich WN. Child Sexual Behavior Inventory: Professional Manual. Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources Odessa; 1997.

20. Achenbach TM. Integrative Guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991.

21. Achenbach T. Manual for the CBCL/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991.

22. Friedrich WN, Beilke RL, Urquiza AJ. Children from sexually abusive families: a behavioral comparison. J Interpers Violence 1987;2:391-402.

23. Oh K, Lee H. Development of Korean Version of Child Behavior Checklist (K-CBCL). Seoul: Korean Research Foundation Report; 1990.

24. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw; 1994.

25. Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC. Social Class and Mental Illness: Community Study. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Son Inc; 1958.

26. Dubowitz H, Black M, Harrington D, Verschoore A. A follow-up study of behavior problems associated with child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl 1993;17:743-754. PMID: 8287287.

27. Hibbard RA, Hartman GL. Behavioral problems in alleged sexual abuse victims. Child Abuse Negl 1992;16:755-762. PMID: 1393734.

28. Friedrich WN, Urquiza AJ, Beilke RL. Behavior problems in sexually abused young children. J Pediatr Psychol 1986;11:47-57. PMID: 3958867.

29. Cho MJ, Hahm BJ, Kim JK, Park KK, Chung EK, Suh TW, et al. Korean Epidemiologic Catchment Area (KECA) study for psychiatric disorders: prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 2004;43:470-480.

30. Shin JU, Jeong SH, Chung US. The Korean version of the Adolescent Dissociative Experience Scale: psychometric properties and the connection to trauma among Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Investig 2009;6:163-172.

31. Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JD. The 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. IV. Reliability and factorial validity in different languages and cultures. J Psychosom Res 2003;55:277-283. PMID: 12932803.

32. Lewis ME. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook. 3rd Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers; 2002.

33. Wiener JM, Dulcan MK. Textbook of child and adolescent psychiatry. 3rd Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2004.

35. The Humane Society of the United States Accessed April 30, 2013. Available at: http://www.humanesociety.org/issues/pet_overpopulation/facts/pet_ownership_statistics.html.

Table 2

Corrected item-total correlation and alpha coefficient when individual item was deleted for total sample of the CSBI (N=280)