|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 7(2); 2010 > Article |

Abstract

Objective

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) measures various aspects of psychological resilience in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other psychiatric ailments. This study sought to assess the reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (K-CD-RISC).

Methods

In total, 576 participants were enrolled (497 females and 79 males), including hospital nurses, university students, and firefighters. Subjects were evaluated using the K-CD-RISC, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Test-retest reliability and internal consistency were examined as a measure of reliability, and convergent validity and factor analysis were also performed to evaluate validity.

Results

Cronbach's α coefficient and test-retest reliability were 0.93 and 0.93, respectively. The total score on the K-CD-RISC was positively correlated with the RSES (r=0.56, p<0.01). Conversely, BDI (r=-0.46, p<0.01), PSS (r=-0.32, p<0.01), and IES-R scores (r=-0.26, p<0.01) were negatively correlated with the K-CD-RISC. The K-CD-RISC showed a five-factor structure that explained 57.2% of the variance.

The concept of psychological resilience is derived from a previously published psychiatric report investigating children who appeared to be relatively unaffected by adverse life events. Psychosocial researchers have noted that some individuals are able to cope and survive better than others in the face of adverse conditions, and resilience research has focused on factors or characteristics that help individuals manage adversity.1,2 Other studies have focused on the importance of resilience as a protective factor against the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3,4

Resilience, a dynamic process in which individuals display positive adaptive skills despite experiencing significant adversity or trauma,5 is a measure of the ability to cope with stress.6 Resilient individuals have a comprehensive ability to adapt to various work and social situations as well as psychological and physical health states.

The original definition of resilience was framed in terms of a personality trait. More recently, resilience has been redefined as a dynamic, modifiable process. This definition has led to the development of resilience-based interventions and facilitated studies on the outcomes of such interventions.5 The recent literature has focused on the derivation of resilience-based intervention and prevention programs, as well as genetic and other biological effects of resilience.6-8 Psychological resilience is suggested to predict one's physiological response to stress. Thus, resilient individuals are able to use positive emotion to "bounce back" from stressful encounters. For example, researchers found that after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack in New York, USA, resilient people had a more positive emotional response to the event, and these positive emotional responses were associated with a reduced incidence of depression.9,10 Resilience has also been shown to protect against posttraumatic debility in the face of adversity and enhance pharmacotherapy outcomes in depression and anxiety.11 Moreover, resilience may play a key role as a protective factor against depression and other psychiatric disorders.12 Resilience is strongly associated with positive affect, which in turn is positively related to self-esteem.13

In Korea, research on resilience has been relatively uncommon to date, although active interest is growing in positive psychology and resilience among Korean psychiatrists.14,15 Several clinical instruments have been developed to assess resilience.16-19 The Resilience Scale (RS), developed by Wagnild and Young16 in 1993, is a reliable and valid tool to measure resilience and has been used with a wide range of study populations.20 In 2003, Connor and Davidson21 developed a new scale to assess resilience, known as the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). They found the full-scale reliability and validity of the CD-RISC to be psychometrically strong with community populations, primary care and general psychiatric outpatients, and with individuals receiving treatment for generalized anxiety disorder and PTSD.21 The CD-RISC is widely used in Western countries for resilience studies such as those addressing coping with stress and responses to pharmacotherapy for psychiatric and physical illness.11,22 In Asia, however, only one study examining a Chinese population has been published.23 In this study, we aimed to develop and validate a Korean version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (K-CD-RISC), to evaluate its potential for cross-cultural application in Korean subjects.

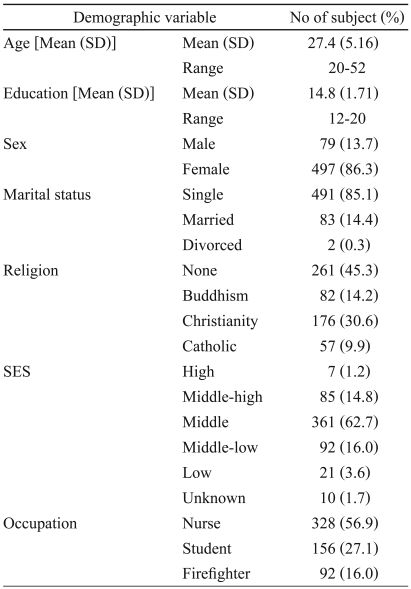

Participants for this study were primarily recruited from two workplaces, a university hospital and a city firefighting unit. Subjects were enrolled as part of a study aimed at evaluating stress and psychiatric symptoms. Interested workers were eligible to participate if they met the following inclusion criteria: age between 18 and 65 years, the ability to give written informed consent, and the ability to read and write Korean. The exclusion criteria were as follows: evidence of cognitive impairment or a psychiatric history of a psychotic disorder. In total, 886 participants were initially included in the study. We excluded 310 subjects due to missing data in at least one item on the K-CD-RISC, yielding a final sample of 576 (328 nurses, 156 students, and 92 firefighters). Women comprised the majority of the sample (86.3%) and the mean age of participants was 27.4 years [standard deviation (SD)=5.16](Table 1). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Eulji Medical Center. All participants provided written informed consent after the procedure had been fully explained.

The scale consists of 25 items, each of which is rated by respondents on a 5-point scale (0='not true at all' to 4='true nearly all of the time') according to the extent to which they agree with each item as it applied to them over the previous month. The total score is achieved by summing all responses, and ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting greater resilience. The preliminary validation study of the CD-RISC demonstrated high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity in a general population and clinical sample.21 The mean score of general population was 80 (SD=12.8); lower scores have been reported in patients with depression and anxiety disorders, with the lowest scores in individuals with PTSD. These studies demonstrated that the CD-RISC is a promising assessment tool for clinical practice and research.6,21 The original CD-RISC has a five-factor structure. Factor 1 represents personal competence, high standards, and tenacity, and implies that one is "not easily frustrated when facing an adverse situation". Factor 2 represents trust in one's instincts, tolerance to negative affect, and strengthening effects of stress. This factor focused on circumspect thinking and decision-making when coping with stress. Factor 3 represents positive acceptance of change and secure relationships with others. This factor relates to adaptability to change. Factor 4 represents control. This factor demonstrates the ability to control the attainment of goals and seek help from others. Factor 5 represents spiritual influences and assessed one's belief in a god. However, In 2007, Campbell-Sills and Stein24 described a four-factor design because the original CD-RISC had an unstable factor structure. These four factors were labeled hardiness, social support/purpose, faith, and persistence.

Two Korean psychiatrists who were fluent in English translated the CD-RISC into Korean, after which two other psychiatrists translated the Korean version back into English. Both versions of the CD-RISC were reviewed by the original developer. The translation and back-translation procedure was repeated until the back-translation was sufficiently similar to the original scale.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a 21-item self-administered questionnaire, was developed to assess the severity of subjective depressive symptoms.25 Each response is scored from 0 to 3, with 3 representing the greatest severity (total possible scores range from 0 to 63). The Korean version of the BDI has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Cronbach's α 0.93, test-retest reliability coefficient r=0.91, consistency coefficient=0.85).26

Impact of the Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) was developed by Weiss and Marmar.27 The original IES28 is a 15-item self-report measure used to assess the frequency of two PTSD symptoms (7 items address intrusion and 8 address avoidance) associated with the experience of a traumatic event. However, the original IES did not address hyperarousal symptoms, and 5 items related to hyperarousal were added to the revised version. IES-R items are rated on a 5-point scale (0 to 4) and evaluate the severity of symptoms experienced during the previous week. Korean versions of the IES-R has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Cronbach's α 0.93, test-retest reliability coefficient r=0.91).29

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was developed by Cohen et al.19 in 1983.

The PSS is a self-reported measure of global stress and measures the extent to which people find their life unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overwhelming. It consists of ten questions rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "never" to "very often" (item score range: 0 to 4, total score range: 0 to 40). The Korean version of the PSS was previously shown to have an internal consistency of 0.82.30

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) assesses global attitudes toward the self (i.e., the sense of self-worth and self-acceptance).31 This scale is a 10-item self-report measure. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree). Item ratings are summed to yield a total score that ranges from 10 to 40; higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. The RSES has high reliability with adolescent boys and young adult samples. Cronbach's α values were 0.88 for the English version and 0.79 for the Korean version.32

1) Subjects' demographic characteristics were assessed. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize CD-RISC scores across the sample population by age, sex, marital status, religion, educational level, and socioeconomic status.

2) To assess reliability and internal consistency, item-total item correlation was assessed using Cronbach's α coefficient. Test-retest reliability was calculated using Pearson's correlation coefficient.

3) The concurrent validity between the K-CD-RISC and other measures (the BDI, the IES-R, the PSS, the RSES) were evaluated using Pearson's correlation coefficients.

4) An exploratory factor analysis was conducted using a varimax rotation.

All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software platform for Windows, version 14.0. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

In total, 886 participants were initially recruited for this study. We excluded 310 subjects who had missing data for at least one item on the K-CD-RISC, yielding a final sample of 576 subjects. The mean subject age was 27.4 years (SD=5.16, range=20-52). Eighty-five percent were single, and the mean level of education was 14.8 years (SD=1.71). Other demographic characteristics (sex, religion, socioeconomic status) are shown in Table 1.

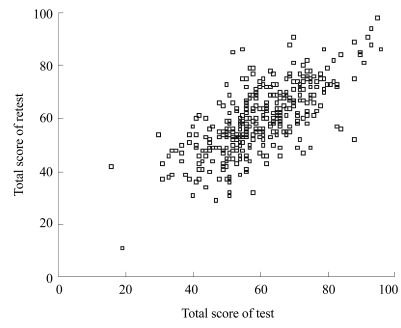

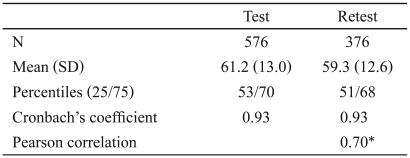

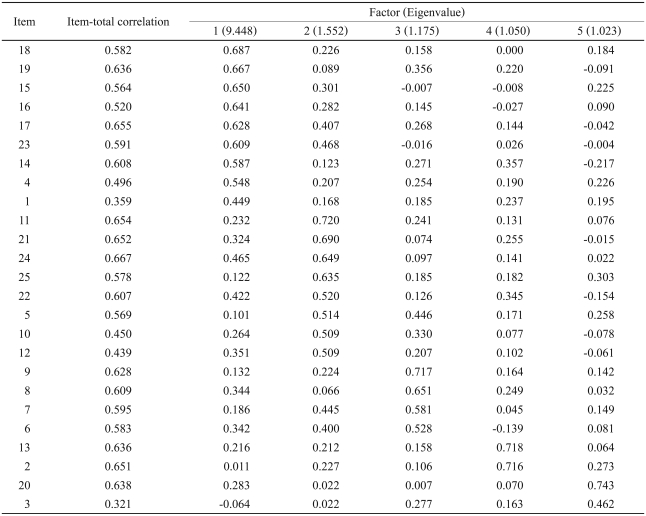

Cronbach's α was 0.93 at baseline and the item-total item correlation ranged from 0.19 to 0.73 (Table 2). These data provide evidence of the internal consistency of the scale. Test-retest reliability was examined 2 weeks later. Although we attempted to retest all participants (n=886), we were only able to do so for 376 subjects (43%). The demographic characteristics of this subsample were not different from the original sample (p<0.05). The test-retest reliability was 0.70 (p<0.01). The mean±SD scores at the first test (61.2±13.0) and retest (59.3±12.6) were highly concordant (Figure 1).

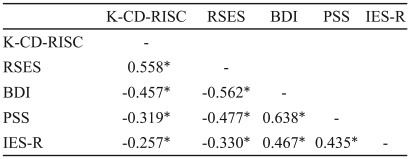

Convergent validity was assessed by comparing the K-CD-RISC with the RSES, the BDI, the PSS, and the IES-R. The total score of the K-CD-RISC was positively correlated with the RSES (r=0.56, p<0.01) and was negatively correlated with the BDI (r=-0.46, p<0.01), the PSS (r=-0.32, p<0.01), and the IES-R (r=-0.26, p<0.01) (Table 3).

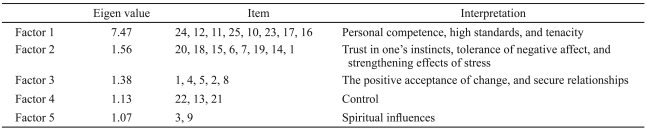

The explorative factor analysis with a varimax rotation on the items of the K-CD-RISC showed that five factors explained 53.1% of the total variance. These factors had eigenvalues greater than 1.0. Factor 1 explained 38.0% (eigenvalue: 9.45) of the variation in the scores of the K-CD-RISC. Factors 2, 3, 4, and 5 accounted for 6.2% (eigenvalue, 1.55), 4.7% (eigenvalue, 1.18), 4.2% (eigenvalue, 1.05), and 4.1% (eigenvalue, 1.02), respectively, of the variance. Table 4 shows the five factors with their eigenvalues and the percentages of variance explained by each (Table 4).

In the present study, we found that the K-CD-RISC exhibited good reliability and validity. Internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the K-CD-RISC was 0.93; this coefficient was within the optimal range for this value and consistent with the Cronbach's α of 0.89 reported for the original CD-RISC. The test-retest reliability of the K-CD-RISC was determined to be 0.70 (p<0.01) via Pearson's correlation.

K-CD-RISC scores were positively correlated with self-esteem and negatively correlated with depression, posttraumatic stress, and perceived stress, similar to what was observed with the initial characterization of the CD-RISC (PSS, r=-0.32, p<0.01). Psychological resilience can predict the physiological response to stress, and resilient individuals are able to use positive emotion to "bounce back" from stressful encounters. Resilience protects against posttraumatic debility in the face of adversity and enhances pharmacotherapeutic outcomes for depression and anxiety.11 Resilience is a protective factor against depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other psychiatric disorders,12 and is strongly associated with positive affect, which in turn is positively related to self-esteem.13 The correlation patterns we observed confirm our hypotheses and provide convincing evidence regarding the validity of the K-CD-RISC among the Korean subjects.

In our study, five components with eigenvalues greater than 1.00 were extracted, which explained 57.2% of the variance in baseline K-CD-RISC scores, consistent with the original studies on the CD-RISC structure. The first factor, which accounted for 38.0% of the variation, was identified as hardiness, and was represented by nine items on the questionnaire. Factors 2, 3, 4, and 5 explained 6.2%, 4.7%, 4.2%, and 4.1% of the variation, respectively. As noted, the first factor was hardiness (including items 18, 19, 15, 16, 17, 23, 14, 4, and 1). The second factor was persistence (items 11, 21, 24, 25, 22, 5, 10, and 12). The third factor was optimism (items 9, 8, 7, and 6), the fourth factor was support (items 13 and 2), and the fifth factor was being spiritual in nature (items 20 and 3). The reliability of factors 1-5 according to Cronbach's α was 0.87, 0.87, 0.58, 0.59, and 0.25, respectively (Table 5).

Factor 1 representing hardiness implied that the subject was "not easily frustrated when facing an adverse situation and had strong internal belief or boldness". The first factor included all items from factor 1 (hardiness) from the original CD-RISC in addition to items 15 and 23. In the original article, items 15 and 23 were "I can make decisions that are unpopular or difficult to others" and "I like challenges," respectively. Some aspects of the first factor in our study were implicated in factor 4 (persistence) of the original CD-RISC. Decision-making requires conviction and propulsive force, but "difficulty" was more closely related to endurance. As Korean participants focused more on "decision-making" than on "difficulty," items 15 and 23 reflected aspects of hardiness. Factor 2 was identified as "persistence." Factor 2 included a large portion of items from factor 4 (persistence) of the original study as well as items 21 and 22. This factor focused on tolerance to negative affect, the strengthening effects of stress and circumspect thinking, and decision-making when coping with stress. Factor 3 represented optimism. Optimism is the feeling of being hopeful about the future or about the chances of success of a particular event. Items involved in factor 3 included "see the humorous side of things", "coping with stress strengthens", "tend to bounce back after illness or hardship", and "things happen for a reason, whether good or bad". Item 9, 8, 7, and 6 were all related to optimism. Factor 4 represented support and implied the ability to receive help from another. Items involved in factor 4 were "know where to turn for help" and "close and secure relationships" Social support and meaningful relationships contribute to resilient outcomes.

Factor 5 represented spiritual influence, but two items (items 20 and 3) did not load on any factor, and the Cronbach's α of factor 5 was relatively low (0.25). In the original study, item 3 ("sometimes fate or God can help") was related to spiritual influence. Spirituality correlates with closeness to God and feelings of interconnectedness in the world and between living things.33,34 This concept is based on Christian values. However, item 3 may have had a different meaning to Korean subjects because the word 'God' was partially lost in translation. Many Korean subjects interpreted item 3 as a question about luck, chance, or things out of their control, and thus is may not have reflected spiritual influence. Therefore, future use of this scale to should include amendments to items 20 and 3. Our results differed from assessments of the original CD-RISC. The original study by Connor and Davidson resulted in a five-factor solution, whereas in the Chinese version a three-factor structure (tenacity, strength, optimism) explained 45% of the variance.23 Campbell-Stills and Stein24 reported that a four-factor structure did not include spiritual influence, consistent with what we report here. Resilience protects individuals against adversity, and the concept of resilience is thought to be universal. However, cultural differences arise due to distinct historical, social, and geological environments, and the concept of resilience may differ across cultures. This may explain why the K-CD-RISC had a different factor structure than the original United States version of the scale.21

The mean CD-RISC scores in the general population, primary care patients, psychiatric outpatients, patients with generalized anxiety disorder, and patients with PTSD in the US were 80.4 (SD=12.8), 71.8 (SD=18.4), 68.0 (SD=15.3), 62.4 (SD=10.7), 47.8 (SD=19.5), and 52.8 (SD=20.4), respectively.21 In our study, the mean score on the K-CD-RISC was 61.2 (SD=13.0). This discrepancy might be attributable to subjects suffering from mild or moderate anxiety and depressive symptoms who were not excluded, and to different socioepidemiological variables such as age, sex, religion, and education. Some variation is likely to occur due to cultural differences.

The present findings must be cautiously interpreted considering the following limitations. First, while convergent validity was demonstrated, divergent validity was not evaluated. Second, the study subjects were not recruited randomly from the general population and included only university students, hospital nurses, and firefighters. The study sample consisted of healthy, young (mean=27.4 years of age, SD=5.16) subjects, mostly female (91%) and unmarried. Thus, generalizing the results across the general population would be difficult.

In conclusion, the K-CD-RISC had good psychometric properties and can be used as a reliable and valid tool to assess resilience, although some cultural variation was apparent. Further studies are needed to fully evaluate the K-CD-RISC, including its application to the general population, primary care patients, psychiatric outpatients, patients with PTSD, and those with other special psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (E00045 & 2009-0076274).

References

1. Garmezy N, Streitman S. Children at risk: the search for the antecedents of schizophrenia. Part I. Conceptual models and research methods. Schizophr Bull 1974;14-90. PMID: 4619494.

2. Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:598-611. PMID: 3830321.

3. Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol 2004;59:20-28. PMID: 14736317.

4. King LA, King DW, Fairbank JA, Keane TM, Adams GA. Resilience-recovery factors in post-traumatic stress disorder among female and male Vietnam veterans: hardiness, postwar social support, and additional stressful life events. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;74:420-434. PMID: 9491585.

5. Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev 2000;71:543-562. PMID: 10953923.

6. Connor KM. Assessment of resilience in the aftermath of trauma. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(Suppl 2):46-49. PMID: 16602815.

7. Luthar SS, Brown PJ. Maximizing resilience through diverse levels of inquiry: prevailing paradigms, possibilities, and priorities for the future. Dev Psychopathol 2007;19:931-955. PMID: 17705909.

8. Vaishnavi S, Connor K, Davidson JR. An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatry Res 2007;152:293-297. PMID: 17459488.

9. Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J Pers Soc Psychol 2004;86:320-333. PMID: 14769087.

10. Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, Barrett LF. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. J Pers 2004;72:1161-1190. PMID: 15509280.

11. Connor K. Fluoxetine in post-traumatic stress disorder. Randomised, double-blind study. Br J Psychiatry 1999;175:17-22. PMID: 10621763.

12. Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1987;57:316-331. PMID: 3303954.

13. Benetti C, Kambouropoulos N. Affect-regulated indirect effects of trait anxiety and trait resilience on self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences 2006;41:341-352.

14. Choi SW. Positive therapy: positive psychology in clinical practice. Korean J Str Res 2007;15:227-234.

15. Kim W. Hope or optimism as a characteristic factor in positive psychology. Korean J Str Res 2007;15:199-204.

16. Wagnild GM, Young HM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Meas 1993;1:165-178. PMID: 7850498.

17. Block J, Kremen AM. IQ and ego-resiliency: conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;70:349-361. PMID: 8636887.

18. Ahern NR, Kiehl EM, Sole ML, Byers J. A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 2006;29:103-125. PMID: 16772239.

19. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385-396. PMID: 6668417.

21. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 2003;18:76-82. PMID: 12964174.

22. Davidson JR, Payne VM, Connor KM, Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Hertzberg MA, et al. Trauma, resilience and saliostasis: effects of treatment in post-traumatic stress disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;20:43-48. PMID: 15602116.

23. Yu X, Zhang J. Factor analysis and psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) with Chinese people. Social Behavior and Personality 2007;35:19-30.

24. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress 2007;20:1019-1028. PMID: 18157881.

25. Beck AT, Steer RA. Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol 1984;40:1365-1367. PMID: 6511949.

26. Rhee M, Lee Y, Park S, Sohn C, Chung Y, Hong S, et al. A standardization study of Beck depression inventory I; Korean version (K-BDI): reliability and factor analysis. Korean J Psychopathol 1995;4:77-95.

27. Weiss DS. In: Wilson JP, Tang CSThe Impact of Event Scale. , editor. Cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD. 2007,New York: Springer, p. 219-238.

28. Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979;41:209-218. PMID: 472086.

29. Lim HK, Woo JM, Kim TS, Kim TH, Choi KS, Chung SK, et al. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. Compr Psychiatry 2009;50:385-390. PMID: 19486738.

30. Ha YS, Jeong GH, Kim SJ. Relationships Between Perceived Stress During The Maternal Role Attainment Process And Health-Promoting Lifestyle Practice Research Institute of Nursing Science. 1990,Ewha Womans University.

31. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. 1965,NJ: Princeton University Press Princeton.

32. Jeon B. Self-esteem: a test of its measurability. Yonsei Journal 1974;11:107-130.

33. Hill PC, Pargament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality. Implications for physical and mental health research. Am Psychol 2003;58:64-74. PMID: 12674819.